True treasures adorn the Staufian monastery church in Lobenfeld, Germany in the Rhine-Neckar district: Wall paintings from bygone days are partially preserved, but not yet thoroughly researched. Almost 90 years old, Doris Ebert still works tirelessly to bring some well-deserved attention to these works of art.

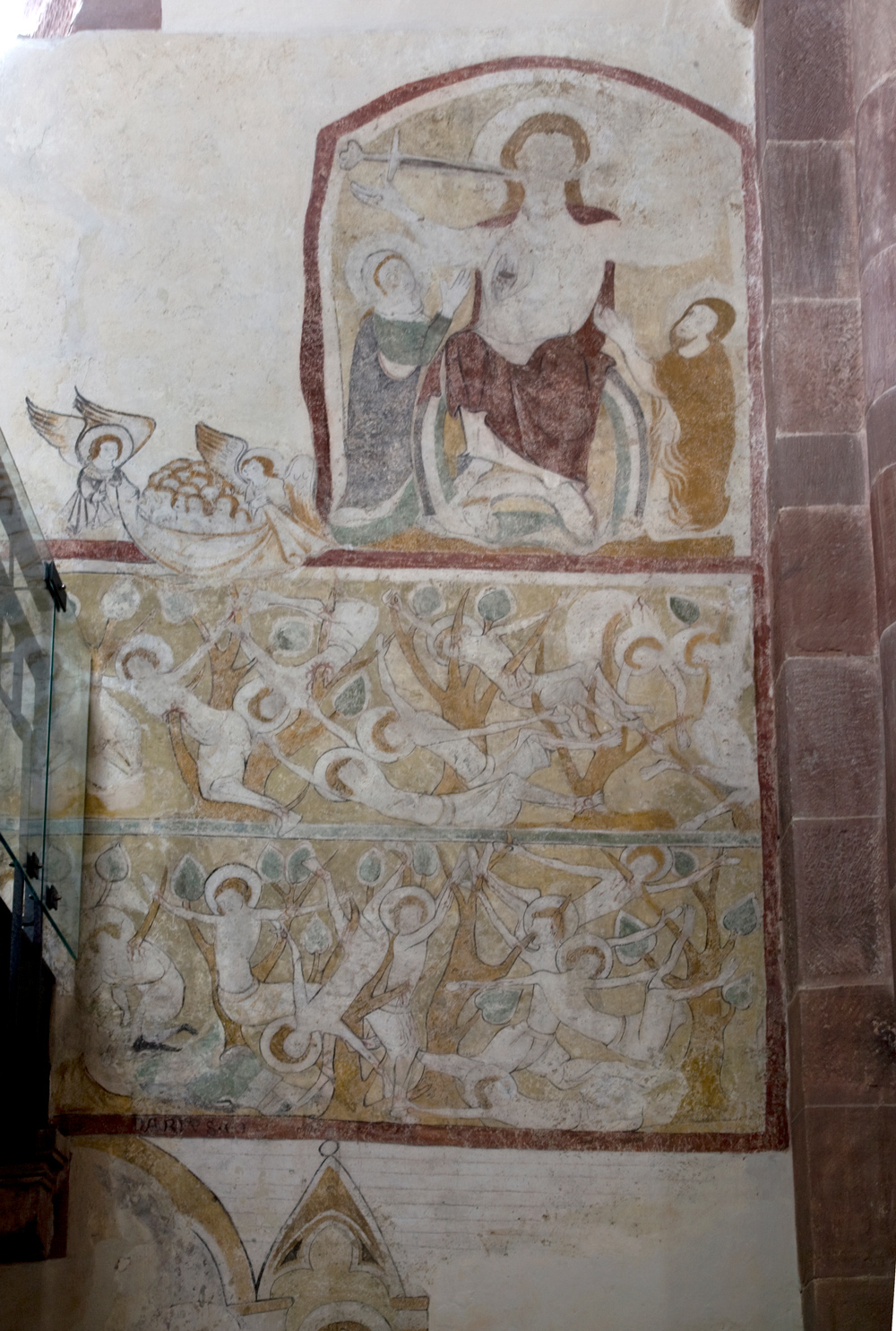

The artworks decorating the cold church walls are pale. Merely a few low hanging lamps shed a warm light on the paintings. Fragments of colour command patience, knowledge and imagination. Scarcely recognizable outlines of a man and two lions: Daniel in the Lion’s Den. Beneath it, the paintings of twelve individuals. The Twelve Apostles? Doris Ebert shakes her head no. The wise woman with her neatly combed back white hair has known better for a long time. Looking closer at the southern wall of the choir room in Lobenfeld’s monastery church and at the mural paintings stemming from around 1230, one recognizes figures of women among the people depicted—and the portrait of a crowned man holding a scepter, an emperor or a king. In front of him, however, the saints stand in a row. “It reads like a warning from the turbulent times of contemporary history and church politics: ‘First the church, then the king.’ In a nunnery!,” says the 89-year-old.

The Lobenfeld monastery church, a massive Staufian structure, raises up atop a small hill right where the Königstuhl, Kraichgau and Odenwald mountains meet. It is a place of many mysteries. So many that they may even cause despair.

In the 70s, Ebert moved from Heidelberg to Lobenfeld with her husband and their three daughters. Ever since, the monastery church has been a source of constant fascination. A technical translator by trade, Ebert has had an active interest in murals since her childhood thanks in large part to her mother, who made a living as an artist.

Despite a lack of early sources, the Lobenfeld monastery church must have been built before 1145. Augustinian Canons from Frankenthal founded it, perhaps for the women of their community. Around the year 1270, Lobenfeld was a spiritual home to the women of the Cirstercian Order—and from 1436 onwards to the women of the Benedictine-Bursfeldian convention. There are many more chapters to the turbulent past, including Jesuits and English Seventh Day Baptists who came to Lobenfeld. During the Palatine schism, the monastery church fell in the hands of the Protestants; the remaining possessions were given to the Catholics. Another 100 years passed and the nave built by the Cistercians in the mid-13th century was turned into a barn for the Catholic treasury in exchange for the possession of a field. A wall in the triumphal arch separated the church and the choir’s eastern wall was knocked down to make room for a door. The wall fell in 1997.