Discover a wellness clinic located idyllically in Gleisweiler in the southern Palatinate—as enchanted as the one in ‘The Magic Mountain’ by Thomas Mann. From here it is not far to Germany’s only forest shower. Learn about an unusual piece of the history of medicine in the Palatinate.

She was always the first. “Every morning she took a bath with obvious enthusiasm to take away the fear of the cold water that timid patients had,” says a sign about the “courageous bath woman” of Gleisweiler. The photo of a shower head found in the ground and of a ladle hangs right next to the forest shower, which is located somewhat hidden in the Hainbachtal valley. Or rather: in the Hainbach brook. The unusual structure in the middle of the forest is fed by spring water at a temperature of eleven degrees Celsius.

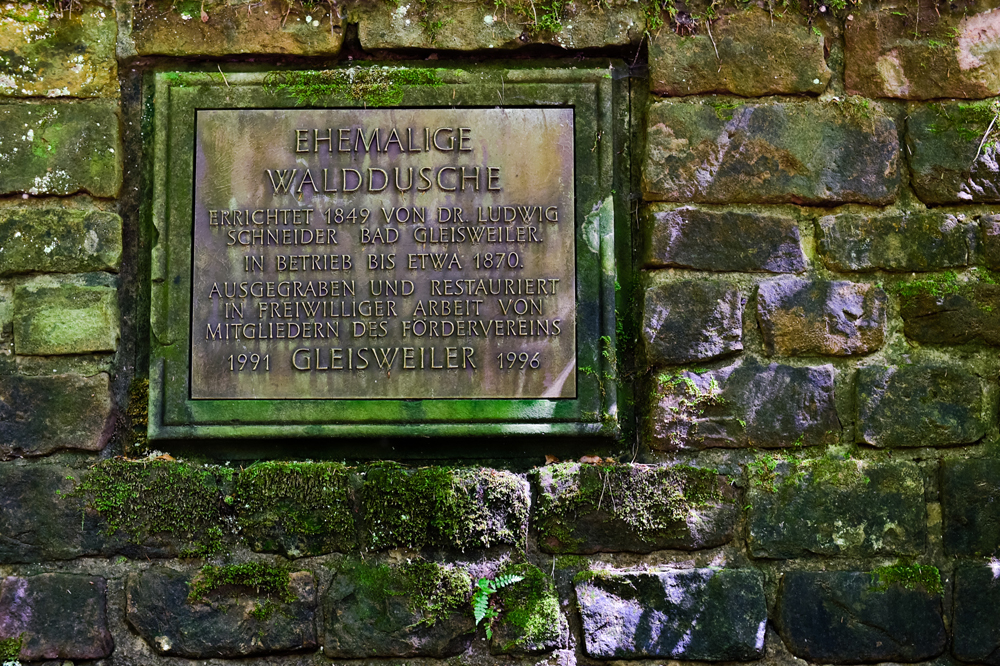

For a long time, Germany’s only remaining forest shower had been forgotten—until mushroom pickers discovered a 70-metre-long water supply channel in the ground between Gleisweiler and Frankenweiler in the summer of 1990. But what exactly were these red sandstones peeking out of the ground? “The forest shower had long been forgotten,” recalls Wolfgang Guth, who had just moved to Gleisweiler at the time. He heard about the curiosity in the forest for the first time from his neighbour. Bit by bit, residents of the village and the mayor Josef Götz discovered the secret of the stone slabs. They founded a support association for the reconstruction of the former forest shower. The result of their efforts is that the natural shower is now installed in the forest again as if it had been there all the time. Cool stream water burbles along in a channel and finally rushes into a basin where you can shower, take a wave bath or tread water. It is now listed as one of the cultural monuments of Rhineland-Palatinate.

Wolfgang Guth is the chairman of the forest shower association, which is also committed to protecting species in the Palatinate Forest. Members of the association have put up nesting boxes and look after them permanently. And they keep the brook and a particular part of it, a fish ladder, free of sand and rock fragments. Young children romp around the burbling water on this hot morning. They squeal with pleasure as they hold their hands in the ice-cold jet of water. Wolfgang looks at the scene and smiles. He will come back in the evening with tools, because he has just noticed that a railing is wobbling and he wants to screw it back into place. He was a master mechanical engineer and this helps a lot. The pensioner knows the construction of the shower and the course of the brook very well.