Hape Kerkeling and Paulo Coelho themselves walked to Santiago de Compostela: making a pilgrimage is in. In Speyer, however, it has been an age-old thing to do. Who would know this better than Hans Ammerich, who searched the archives of the diocese for traces of the religious ramblers.

Some people have a favourite book, others have favourite movies or a favourite pullover. But a favourite certificate, of all things? Hans Ammerich is beaming all over, as a colleague hands him the simple, brown box from the cabinet in the archives. He reveals the document and the atmosphere in the plain functional building of the Diocese of Speyer becomes almost ceremonial. The former director of the archives discovered a document by Louis the Bavarian (1282-1347) that contains the ruler’s arrangements for the property of the so-called Stuhlbrüder brotherhood in Mutterstadt. With a smile, he deciphers the old, beautifully curved handwriting and examines the 700-year-old seal, which is still in a very good condition. “The devout men were here to pray for the spiritual welfare of the kings, emperors and empresses buried in the Cathedral,” Hans explains. In return, they were allocated landed property to live on its profit.

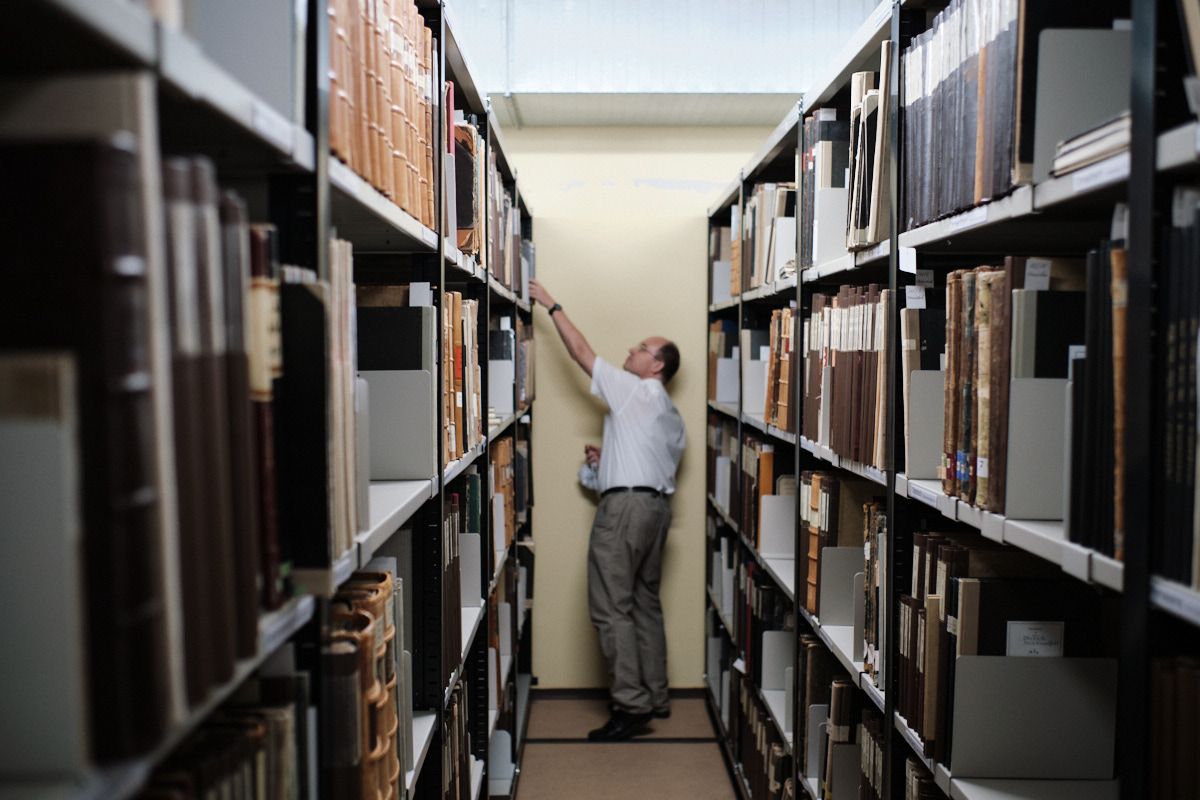

No doubt: the man is passionate about being a historian. His former work place, the archives of the Diocese of Speyer, is somewhat the Palatinate memory of the Catholic Church. Valuable parchment manuscripts are stored here, such as the ‘Speyerer Missale’ from 1343, parish registers and papal bulls as well as unpublished works, files and photographs. Hans was born in 1949 and managed the archives for 35 years. One of his research projects is the St. James pilgrims in the Palatinate. This subject had already been a trend subject when research into it began, some decades ago. It is a subject with an ongoing history, because some 300,000 people per year make a pilgrimage on the Way of St. James according to estimates by the pilgrims’ office in Santiago de Compostela. However, this number represents only the pilgrims on the Spanish part of the track.

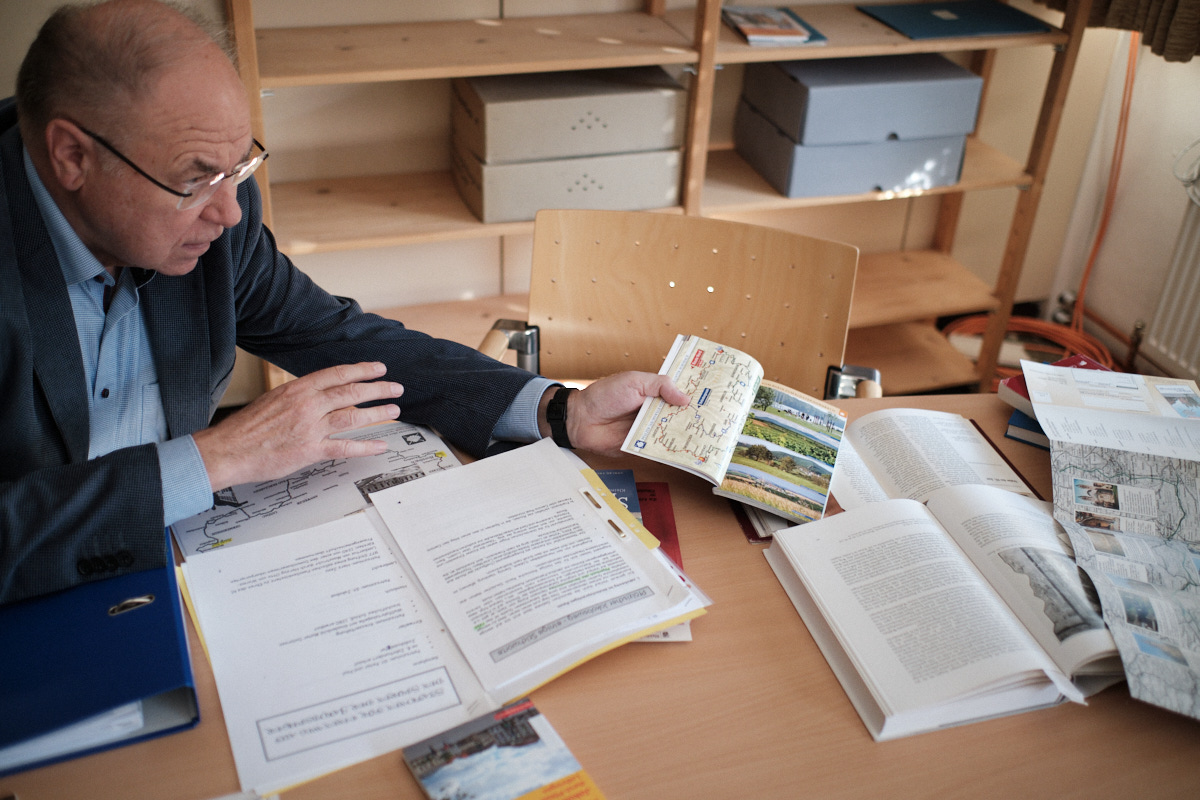

Hans has always known that the Palatinate has ever since been part of the Way of St. James: “The routes for trade and for the armed forces were well developed in this cross-border region and they were relatively safe.” Furthermore, the region has always offered castles, churches and monasteries one after another, which used to attract travellers seeking shelter, accommodation, food and spiritual places for contemplation and prayer. At the end of the 1990s, Hans started with his colleague Susanne Rieß-Stumm to trace the old tracks upon the request of the politician Rainer Rund and the then bishop Anton Schlembach. It was certainly helpful that the then district president Rainer Rund had been the long-standing head of the Pfälzerwald-Verein (Palatinate Forest club). Members of the club look after the tracks with their typical scallop shell markings. The scallop shell is the symbol for all St. James pilgrims and refers to the patron saint of all ramblers, James the Great.