The appearance of the library from the outside with its deep window jambs and the old gate is still very much that of the former convent of nuns, whereas the inside of the reading rooms has been designed in a more functional way, except for the sacred room: The Buchen music school uses the room to hold concerts and do rehearsals. And, upon the library’s invitation, an occasional Klezmer group performs in the small apse with its choir niches that are covered with frescos.

“Priest Herbert selected in a well-directed manner and out of an intellectual motivation—not always in a systematic way though.”

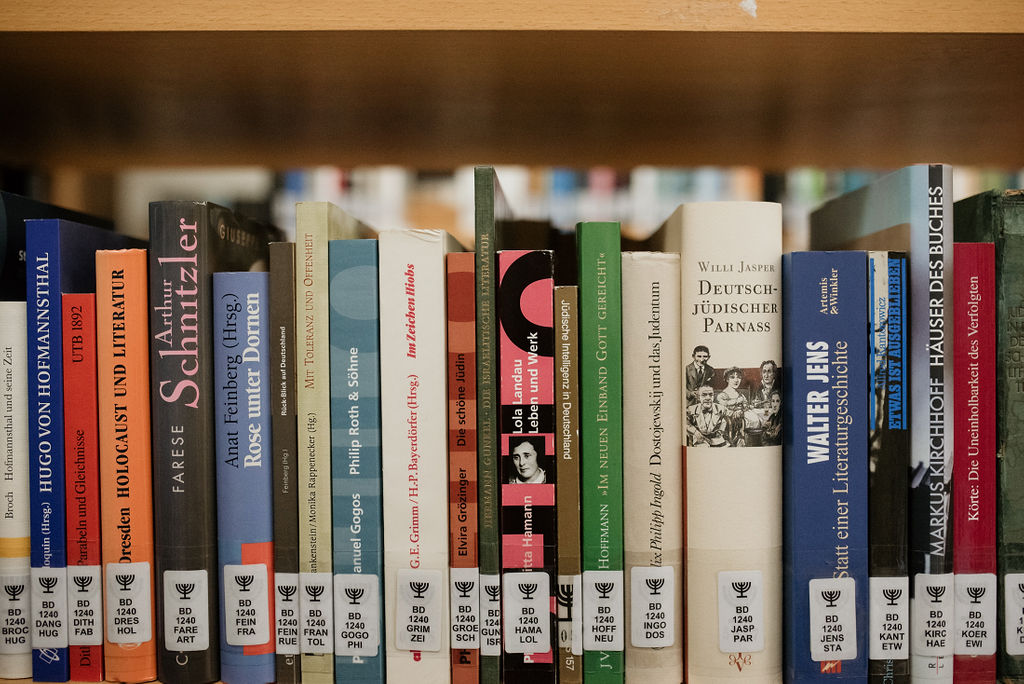

You can borrow from a selection of about 9,000 books plus diapositives and CDs in the library that Hermann adapted over a period of several weekends with the assistance of a team of locals and the Brunswick specialist in Jewish studies Rebekka Denz, drawing up a professional online catalogue. “Priest Herbert selected in a well-directed manner and out of an intellectual motivation—not always in a systematic way though,” says Hermann, who was on hand straight away, when at the end of the 90s there was demand for a voluntary manager for the Jewish library. “Back then, I was just about to go into retirement and I was happy to have a new area of responsibility.”

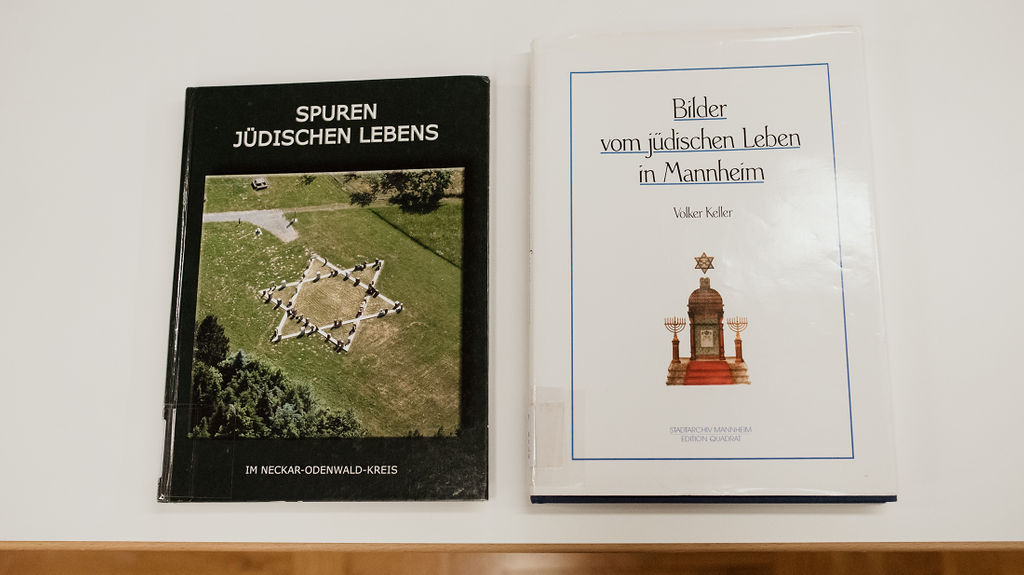

Today the variety of books ranges from scientific papers to fundamental theological issues and cookery and photographic books—around Judaism. “As a child, in the November Pogroms, I saw the furniture being thrown out of the windows of Jewish families,” the former manager of the municipal library recalls the scene. He was born in 1934 in Karlsruhe but grew up in Mannheim. The family settled in the Odenwald in 1945, when his father took on the duty of mayor in Buchen. He hasn’t forgotten the scenes he witnessed in Augartenstraße in Mannheim, neither those with Jewish men and women queuing up along the wall of Mannheim Palace waiting for their deportation to Gurs internment camp in France in 1940. “Something like this must never happen again.”

Hermann officially manages the library of Judaism. The management of the library foundation, however, is done by the town archivist Tobias-Jan Kohler. The foundation is responsible for events, new acquisitions and special projects such as the recent restoration of a hearse that the Jewish community had built for the district cemetery in Bödingen in 1911. This cemetery, like almost every Jewish cemetery in Germany is concealed by an iron grating door. To whom it has been opened, will see one of the most beautiful places in the Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis district: There are over 1,500 graves here, lining up along the gentle hills of a forest. It is centuries old and overgrown with moss—far removed from the rest of the world. “The oldest gravestone is from the year 1628,” explains Tobias-Jan, who was born in 1988, studied history in Düsseldorf and returned to his home region, the Odenwald, to run the Buchen archives.

“There is a current project intending to give the many names of Jewish Buchen citizens back their faces, who were deported or murdered by or escaped the Nazi regime, by means of old glass plate photographs by the photographer Karl Weiß,” says the historian. The Jewish community in Buchen can be traced back to 1337. Tobias-Jan supposes that the burial ground in Bödigheim dates back to the Middle Ages as well. In certain periods, it served as common cemetery for up to 20 parishes—in 1932 it was only used by ten anymore.

In Bödigheim are over 1,500 graves, lining up along the gentle hills of a forest.

And Jacob Mayer? “He wouldn’t have been able to imagine life in a town other than Buchen,” Hermann explains while he guides us to the older part located more at the back of the cemetery. Jacob’s mother is buried here. And Jacob as well—buried here unofficially in June 1939 after he had committed suicide. It was the last funeral in Bödigheim. There is no Jewish community in Buchen anymore. To this day, the gravestone doesn’t have an inscription that holds the memory of Jacob.

The gravestone of Henriette Mayer, Jacob Mayer’s mother.

The dialect poet has left traces anyway: One of the two reading rooms of the library of Judaism features three little show cases from Jacobs merchant shop. Ruins of the Jewish ritual bath, the mikveh, were unearthed in the ground where once the Buchen synagogue stood and a memorial for the victims of the Nazi regime was erected. The square above is named after Jacob Mayer and so are a road and a primary school in Buchen.

Hermann Schmerbeck in the memorial for the victims of the Nazi regime.

A few metres from there, the carnival club Fasenachtsgesellschaft Narrhalla run their multi-coloured house of fools, whose most favourite hymn belongs to the collective memory of the town. You can hear it ringing, for example, from the town’s tower. Its bells play songs three times per day—among them Jacob’s most famous carnival song. “Kerl wach uff, vergeß Dei’ Plog’ (Wake up, fellow, forget nuisance)/ Vergess Dei’ Not und Sorgen (Forget your need and sorrow)! Denk’ daß heut ein froher Tag, Und vergiß das Morgen (Believe it is a joyful day, forget about tomorrow)! Denk, daß einmal nur im Jahr (Beware that only once per year)/ Uns die Gnad’ gegeben (Given is the grace)/ Überschäumend, toll, als Narren (to celebrate the carnival as fools with fun)/ Fastnacht zu erleben (in this place).”

You can find Gerlinde Trunks and Jürgen Streins book about Jacob Mayer here:

https://shop.buchen.de/top-produkte/jacob-mayer.html

www.buecherei-des-judentums.de