For Palatinate locals, a journey to Pennsylvania is a journey to their inner self. To their own language and culture of the past. For this is where the Pennsilfaanisch Deitsche live—people, who emigrated from the Palatinate, and still maintain their old dialect. In this interview, linguist Dr. Michael Werner talks about a form of Palatinate dialect that knows no “alla hopp,” about creepy “Elwedritsche” and about marmot Bert, who recently started living in a Palatinate wine barrel.

Michael Werner is right on the ball. He holds a wooden figure from Pennsylvania into the camera as soon as the video interview starts. It looks scary: a feathered something with a creepy face. It is an “Elwedritsch.” The American mythical creature is not even nearly as funny as its relatives from the Palatinate. “Belzenickel” that Werner shows us immediately afterwards, makes a creepy impression as well: Every year at Christmas, this weird fellow comes to children in Pennsylvania. He is, however, more reminiscent of the grim servant Knecht Ruprecht than of the friendly Saint Nicholas. With these creatures, Michael takes us right into the middle of the history of the Electoral Palatinate and goes on to talk about the traces he has found in the US, points out similarities and refers to connections to as far back as Indian and Germanic mythology. It’s time to bring him back to the present for a moment.

wo sonst: Wilkum, wie bischt? (Welcome, how are you?)

Michael Werner: [laughing] Ganz guud. (Quite fine.)

wo sonst: This is where my knowledge of Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch has already come to an end. Anyway, would I be able to get by with knowledge of the Palatinate dialect in Pennsylvania today?

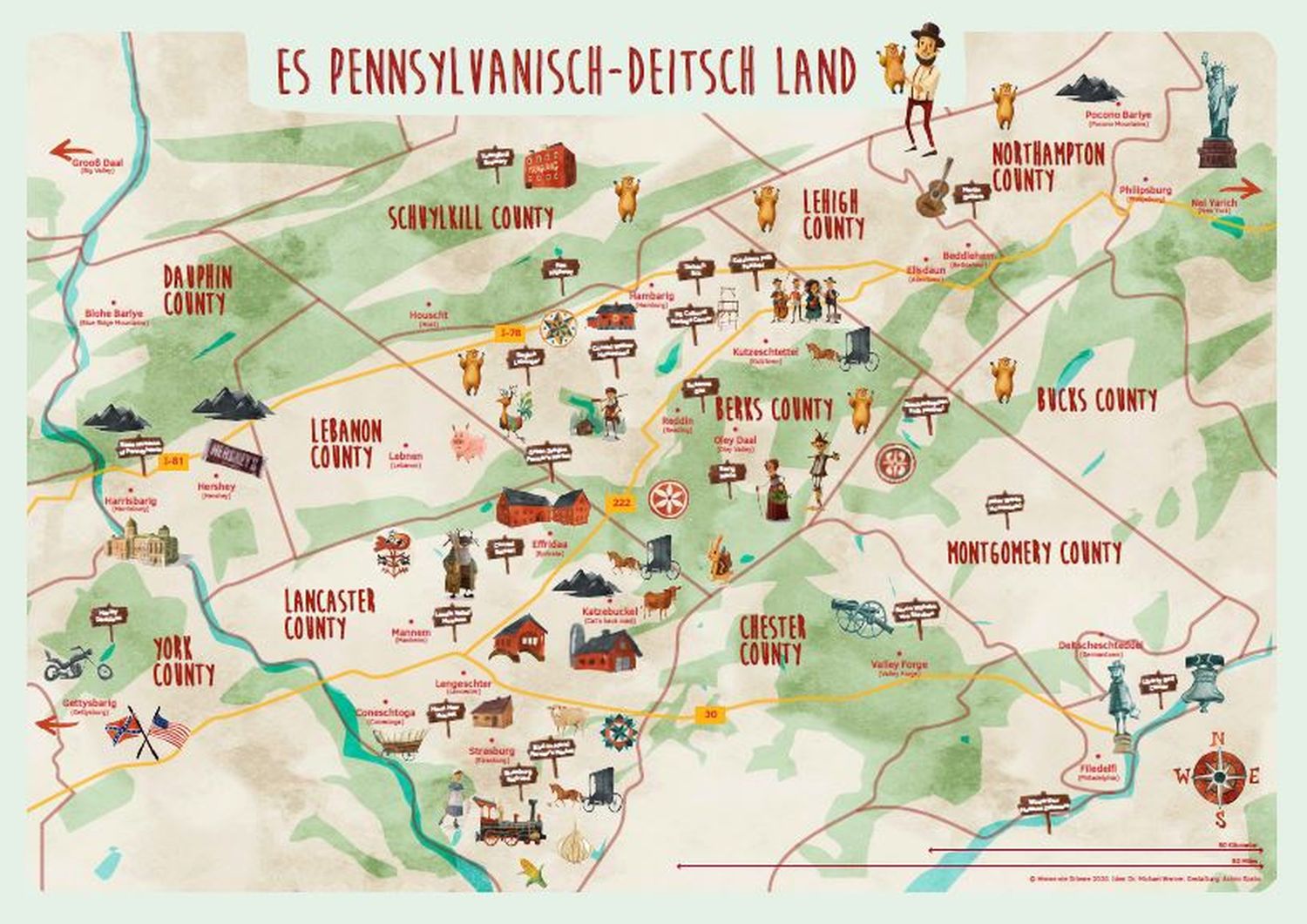

Werner: You’ll be fine as long as you’re in Pennsilfaanisch-Deitschland, the region north of Philadelphia. The Deitsch, or Dutch, which is spoken there, is 80 percent similar to our present-day Palatinate. It equals the Electoral Palatinate dialect that was spoken until the 18th century in an area about 20 kilometres around Mannheim and Heidelberg. But of course there are differences as well.

Listen and learn: A lesson in Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch.

Klicken Sie auf den unteren Button, um den Inhalt von soundcloud.com zu laden.

wo sonst: What are these differences?

Werner: In Deitsch there is no “alla” and hence no “alla hopp!”

wo sonst: You must be joking: Palatinate dialect without “alla hopp?”

Michael Werner: Well, “alla hopp” obviously immigrated to the Palatinate after a number of Palatinate locals had emigrated from it. “Alla hopp” is borrowed from the French “allons” and apparently sneaked into Palatinate not before the end of the 18th century, like many French terms did. The major migration flows had taken place before that, in the 17th and 18th century. So, Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch doesn’t have any French loanwords. In return, a number of English terms slipped in.

wo sonst: Like ‘wilkum’ that sounds almost like ‘welcome?’

Michael Werner: Yes, there are lots of German-American mixtures. Like “mir hickele” (wir hüpfen = we hop) that became “mer dschumbe.” And there are terms, whose meaning changed over time, such as “halt an!” Its original German meaning, “stop,” was turned upside down by the adaptation of the English meaning of “hold on.”