Some thought she was a lazy woman because she did not want to work in the fields. Others thought she was a progressive thinker. Augusta Bender was born in Schefflenz in the Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis district in 1846. She never received the recognition she sought during her lifetime. But since 2020, a museum in her birthplace has been telling the story of the writer, animal rights activist and women’s rights campaigner and has been raising the question what we can learn from her today.

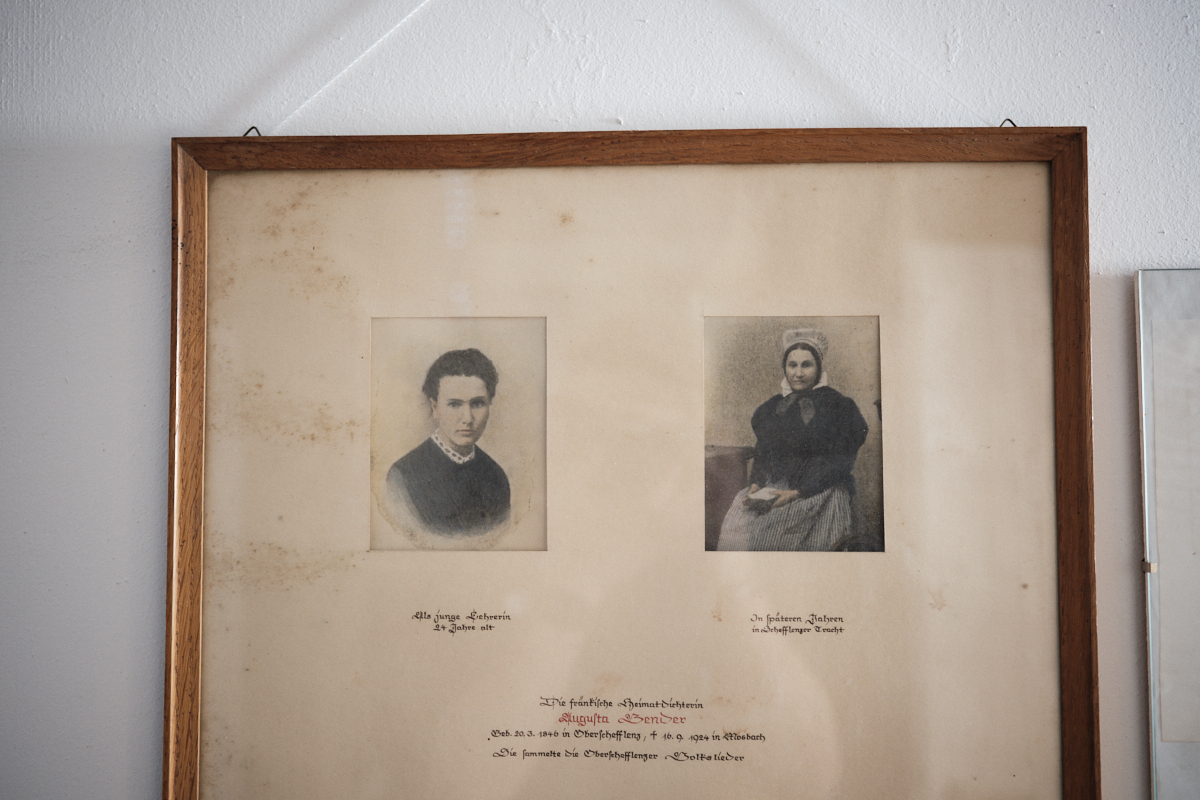

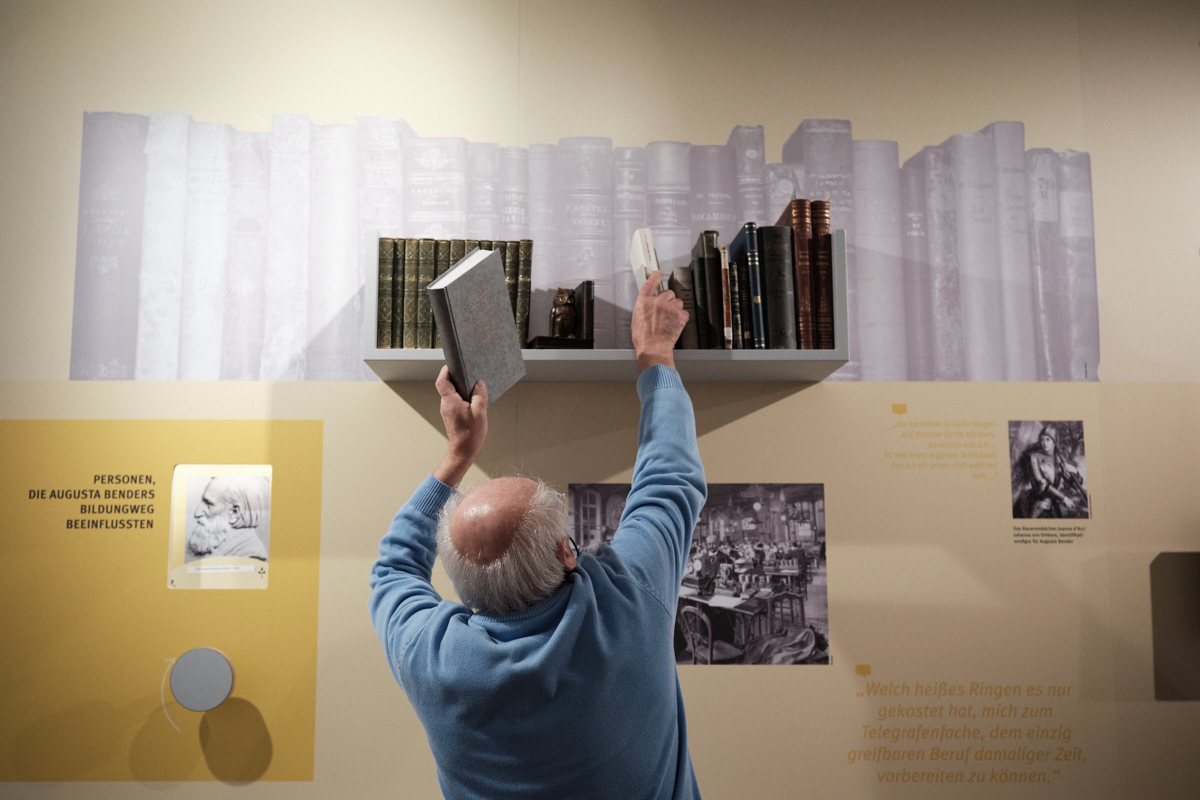

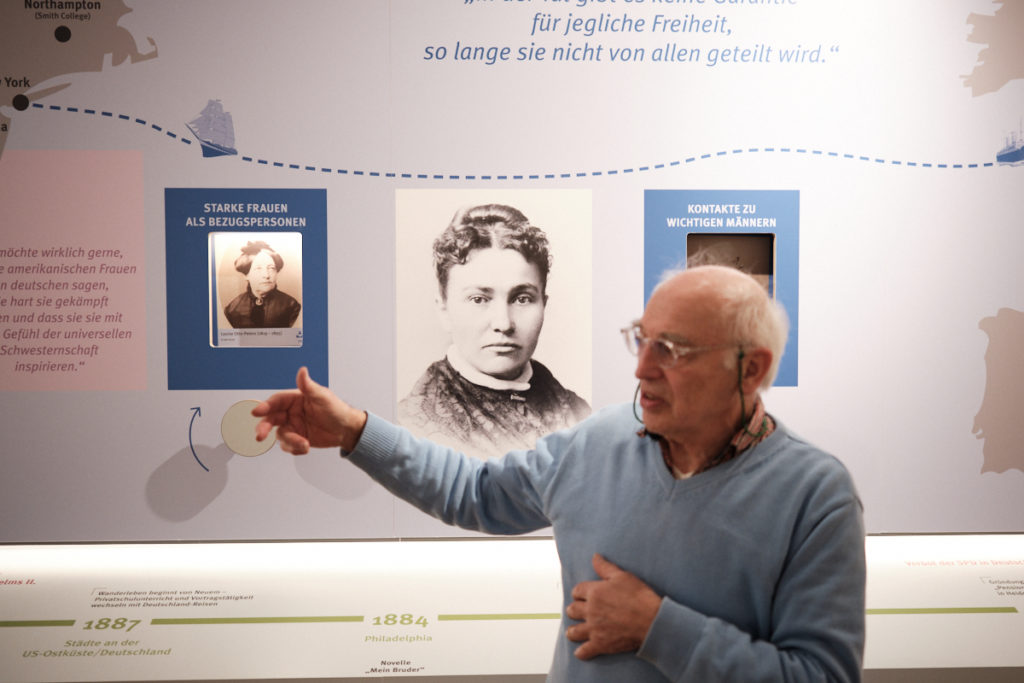

Who was Augusta Bender? Georg Fischer does not have to think long before he answers. “You shouldn’t pin her down to one thing,” he prefaces, then gets going: a farmer’s daughter, failed actress, telegrapher, private teacher, traveller across America, author and explorer of folk songs. The pensioner with the bushy eyebrows lists all the activities Augusta pursued while he stands in front of a photo showing the young writer holding a cat in her arms and laughing. The protection of animals was as close to her heart as women’s rights. “However, she was not a revolutionary, she was a conservative woman.” In the village she was considered a “lazy woman” because she fought for education instead of working in the fields. Her works were not recognised and so she almost starved to death.

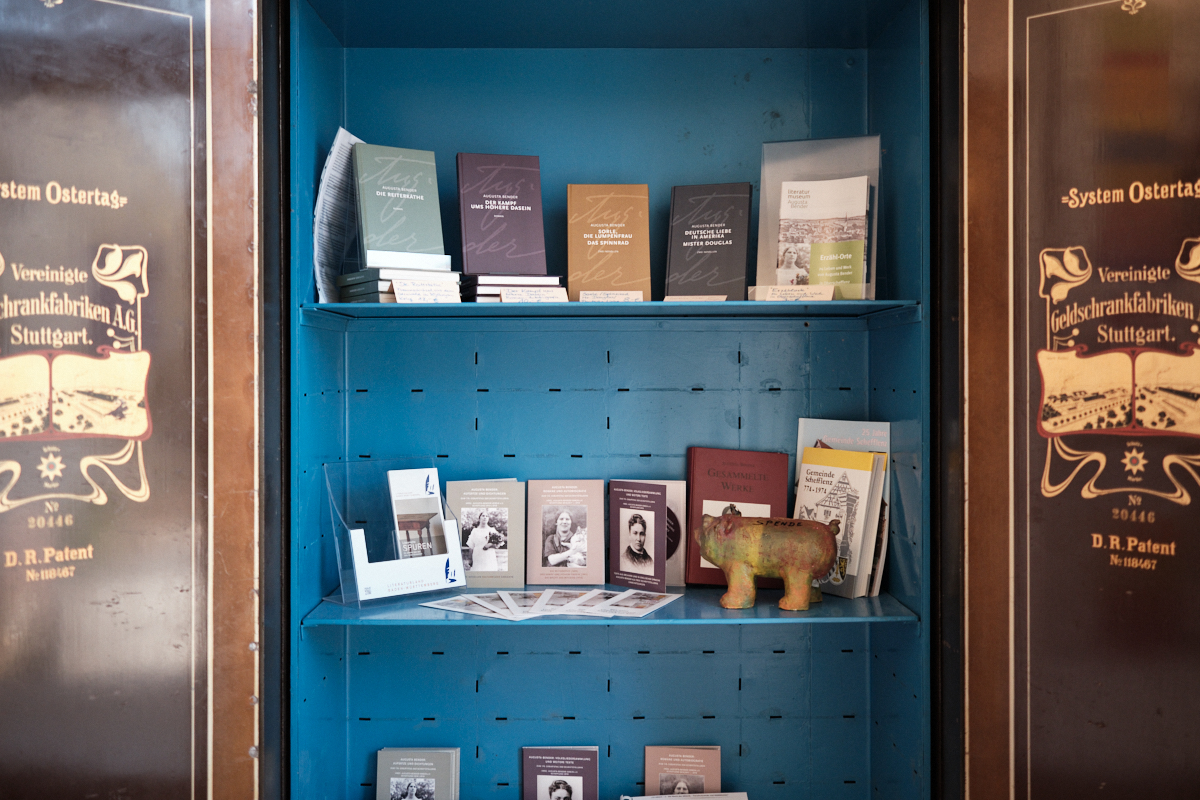

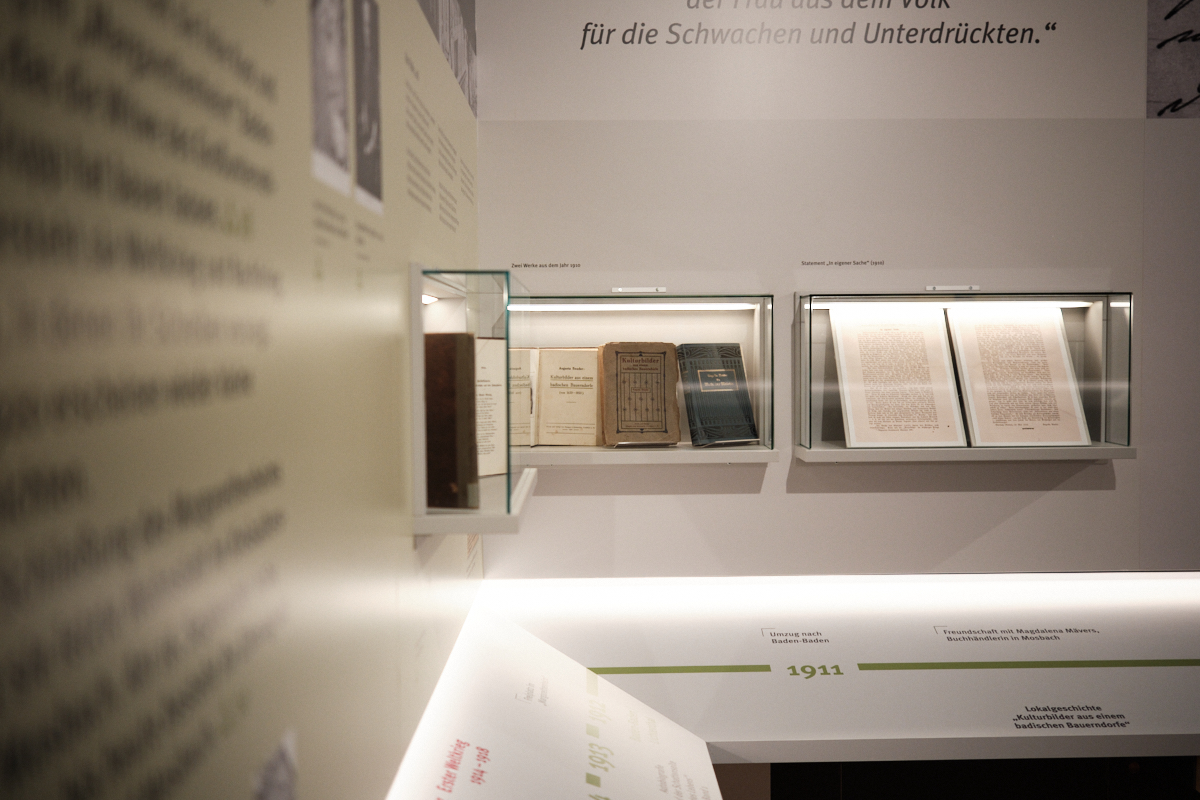

It is these contradictions that fascinate Georg about Augusta Bender. It is largely thanks to him that there is a small museum in her birthplace Oberschefflenz commemorating her today. He discovered the misunderstood writer in 1989 and gradually brought her out of obscurity. He and a few like-minded people founded the Augusta Bender literature museum club in 2017, which has 75 members in the meantime. Three years later, the museum opened in the former land registry office in the middle of the municipality of 1,500 residents near Mosbach. It is one of about 100 literary museums, archives and memorials in Baden-Württemberg. One of the few dedicated to a woman.

Augusta Bender’s life began a couple of streets down from here in 1846. She was born the sixth child of a peasant family. Her mother told her legends and stories, and Augusta became enthusiastic about literature at an early age. At the age of nine, she published a poem in the Odenwälder Boten Gazette and was, from then on, eager for education and for leaving the village. At 16, she ran away for the first time, tried her hand at acting in Mannheim—and failed. This wasn’t to be the only time. She lost her savings years later in the attempt to start a language school in Heidelberg. Even though she was a trained teacher and spoke four languages, she was unable to find a job in Germany. And also as a writer, she was denied the recognition she sought for the rest of her life.