Wolfgang Immel created a museum for photo, film and television technology in Deidesheim. Some 5,000 exhibits reveal the technological cultural heritage of an entire country – and family history.

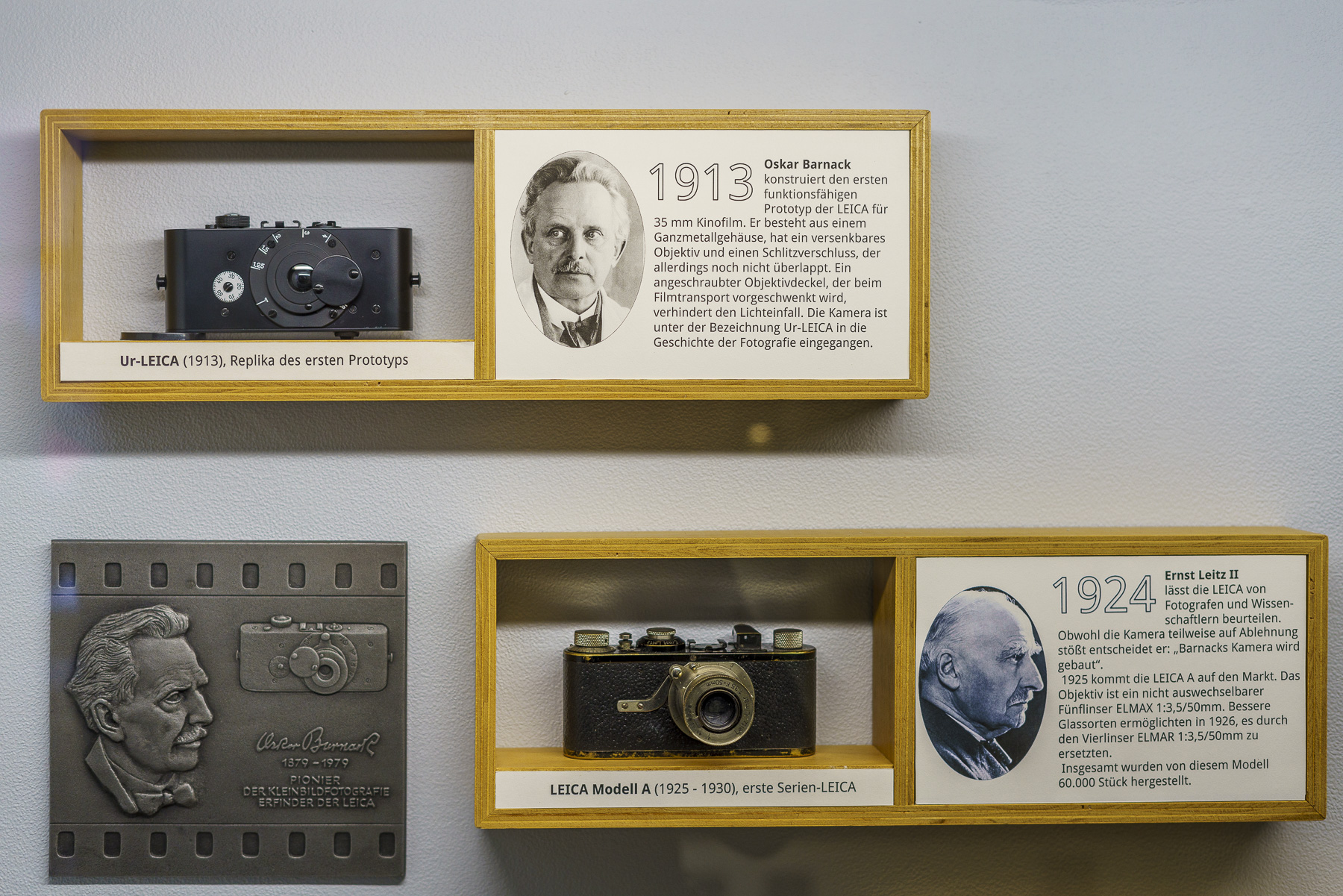

Loads of exhibits reach the museum. They come from people who are just as enthusiastic about the technical equipment as the head of the museum and who have influenced and developed it further – for example from the granddaughter of Oskar Messter, who was the founder of German film technology: The medal that her grandfather was awarded by the Deutsche Kinotechnische Gesellschaft (German cinematographic society) is now placed in a glass cabinet of the Museum für Foto-, Film- und Fernsehtechnik (museum for foto, film and television technology) in Deidesheim. Wolfgang Immel can clearly recall the moment that Oskar Messter’s granddaughter gave him a box with his property: “She said: I really prefer his property being left here.”

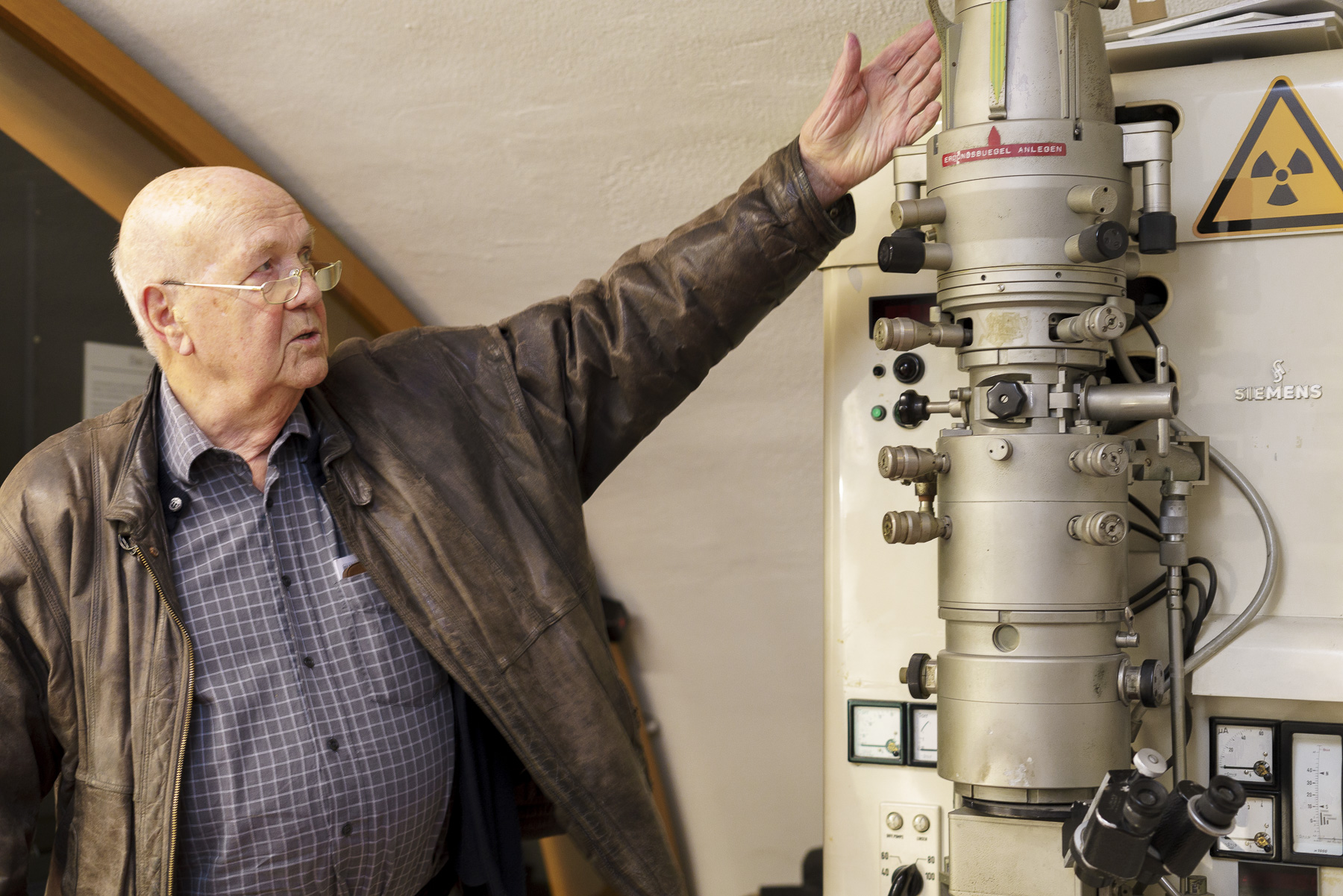

Wolfgang Immel – founder and chair of the Museum für Foto-, Film- und Fernsehtechnik (museum for foto, film and television technology).

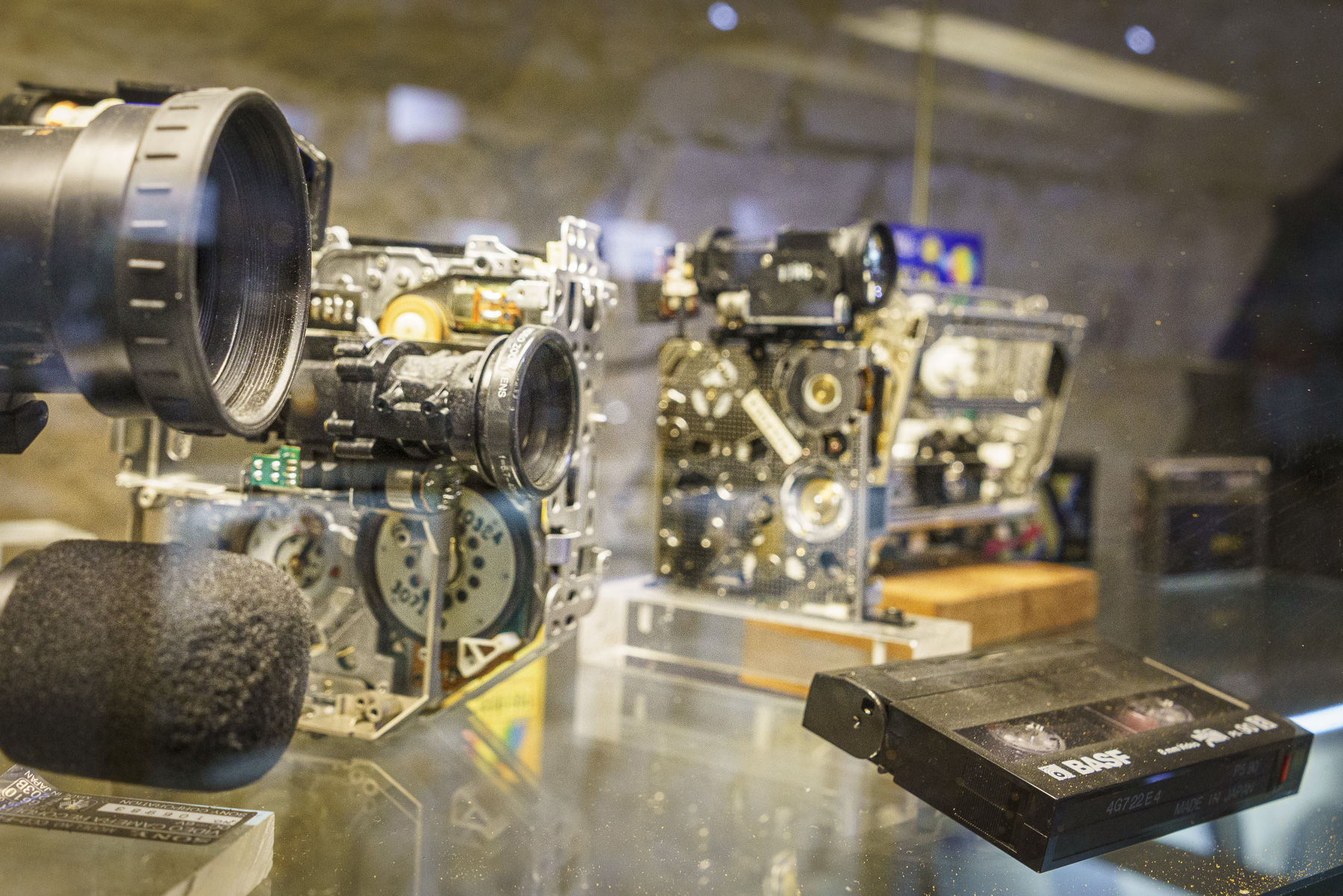

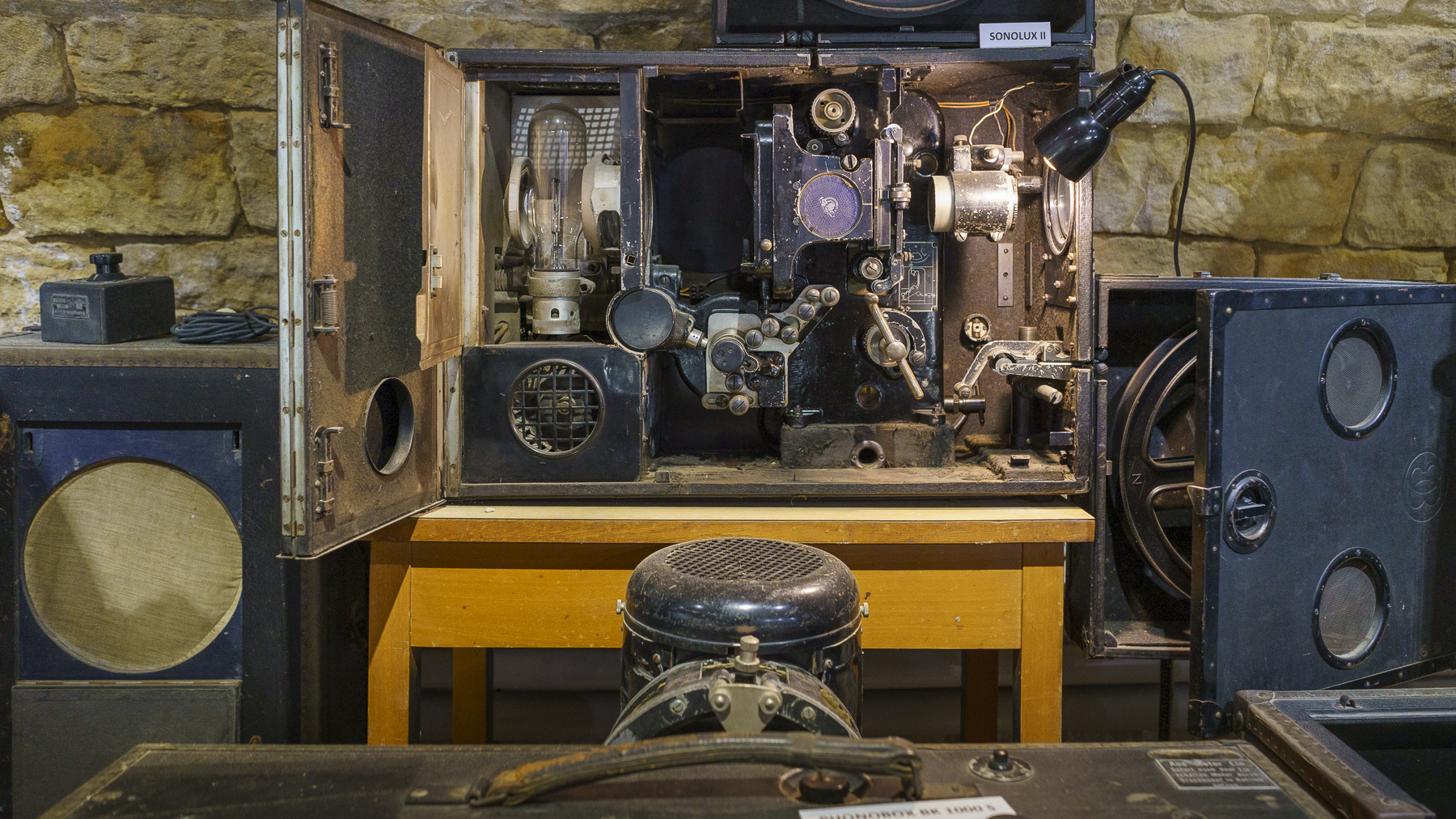

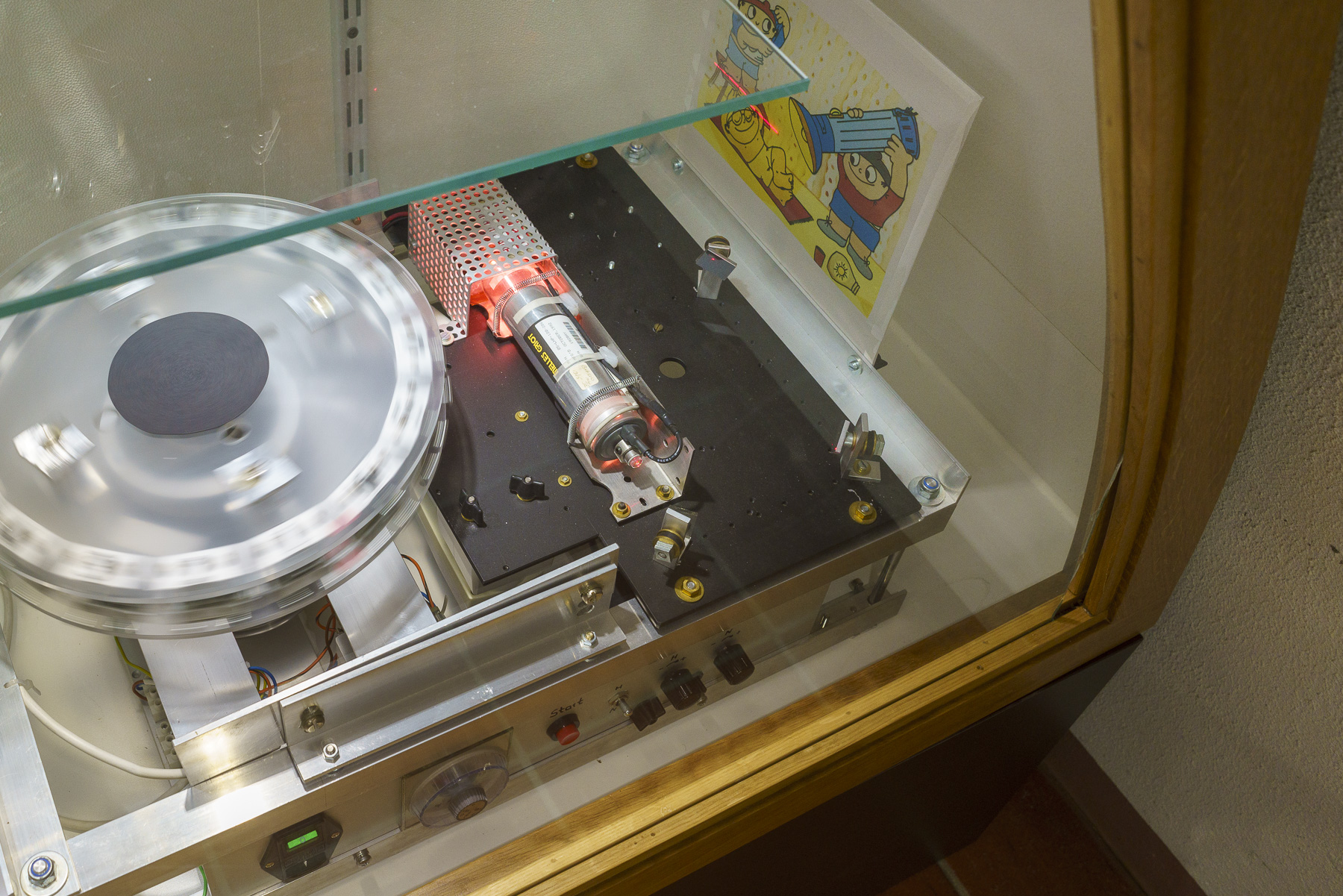

The museum located in a building of the Bürgerhospital-Stiftung foundation close to the historical town hall in the centre of Deidesheim displays about 5,000 exhibits – a collection that is unparalleled in Germany, because the team and the founder and chair, Wolfgang Immel, consider it technical cultural heritage. Handy cameras, heavy projectors, flashes and films – devices everybody knows and, at the same time, a technology that has already been forgotten again. At the entrance, visitors to the museum can operate a television camera, a model still in use in television studios today. Looking through it, you can focus on a plate inside a glass cabinet that says: ‘Der Film hat viele Väter’ (Film has many fathers). The museum tells their stories.

The museum is located in a building of the Bürgerhospital-Stiftung foundation close to the historical town hall in the centre of Deidesheim.

However, all of this once began with a woman: a visit by aunt Luise. She frequented the home of Wolfgang in Limburg an der Lahn and she was a film enthusiast. “My sister and I were fascinated by her,” says Wolfgang. Later, when his wife was given a film camera by her parents for completing her studies, Wolfgang began filming. The technology lover, who came to the region to work as a chemist at BASF, collected more and more items, amounting to a large collection of about 460 film projectors. Udo Zink, a chemist from Ludwigshafen, had collected about the same amount of photo cameras at roughly the same time. The two men met in the 70s at photo and film markets. Their shared interest was the passion for technology and the desire to make their collections accessible to others.