They feel the bassand their hands start singing. The sign choir ‘Voice Hands’ bridges the gap between the worlds of the hearing-impaired and that of the hearing in Frankenthal—setting a political example.

A car that passes by, a bird’s chatter, a mobile ring tone, a low reverberating bass that you can feel—such sound waves are crucial for the five female choir members of ‘Voice Hands’. These waves and eye contact with their singer and choirmaster, Klaus Schwarz, let them know when a song begins.

It is a Monday evening in the communication centre ‘Kommunikationszentrum Frankenthal’, which has been the headquarters of the ‘Landesverband der Gehörlosen’ (the Rhineland-Palatinate association for the hearing-impaired) for 25 years. Daniela Barde from Schifferstadt, Monika Blank from Mannheim, Ursula Menger from Bellheim, Dorothee Reddig from Frankenthal and Daniela Schanzenbach from Ludwigshafen meet here with singer Klaus Schwarz from Schifferstadt.

The ladies of the sign choir Voice Hands: Dorothee Redig, Ursula Menger, Daniela Barde and Monika Blank (not on the photo: Daniela Schanzenbach and Klaus Schwarz).

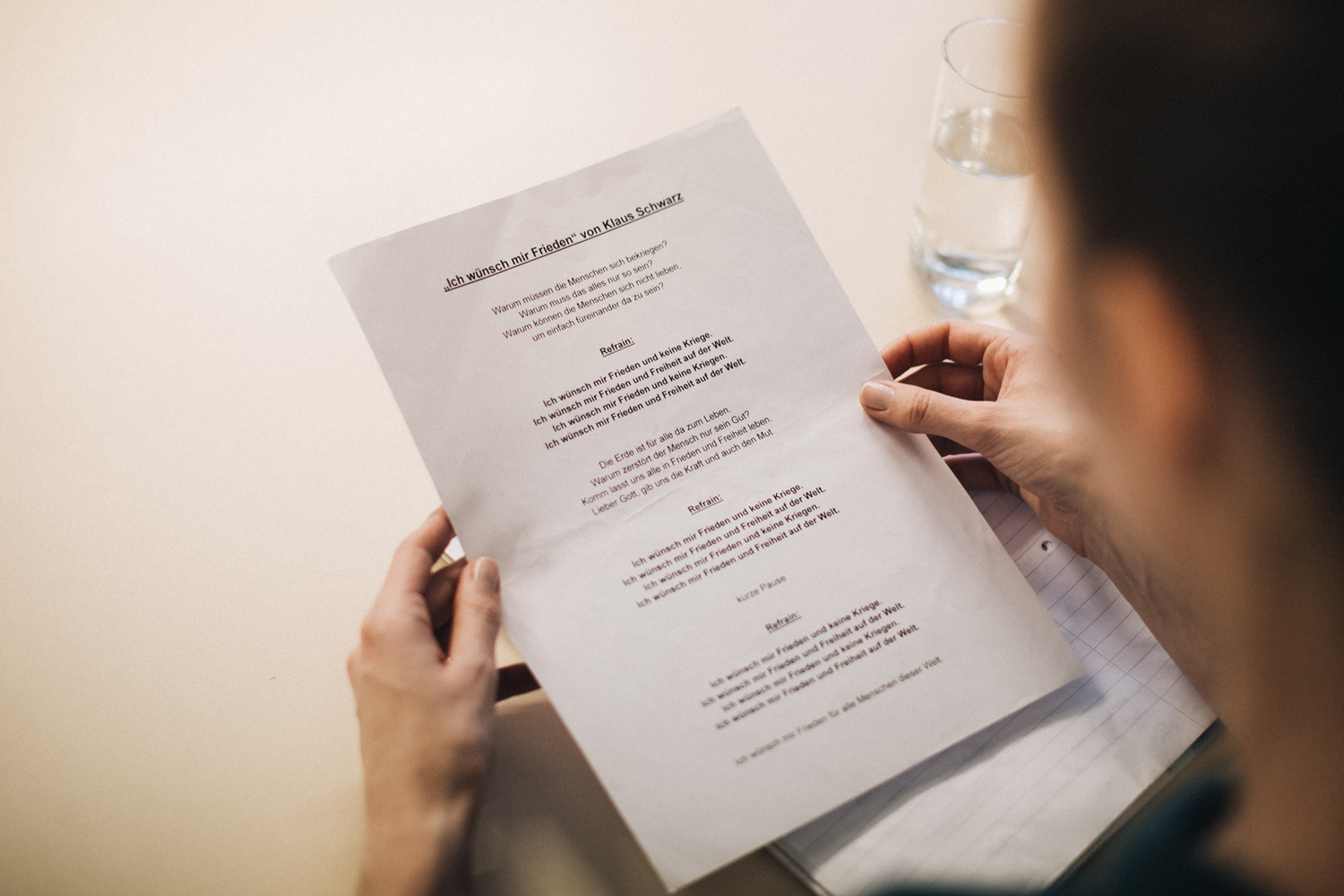

The choir was founded in November 2016. It developed out of an idea that the long-standing friends Daniela Barde and Klaus Schwarz came up with. Daniela was diagnosed with deafness a few months after her birth. Since a few years ago, a hearing aid has enabled the young woman to hear a little bit, although it takes effort. Klaus is a trained roofer, attends one party after another as ‘Schlager Klaus’ (pop song Klaus) and writes songs—for himself as well as under contract to other musicians. Klaus found it “such a shame that Daniela and all the hearing-impaired cannot experience my songs.”

So, Daniela and Klaus presented their idea of a choir in the communication centre. In no time at all, a group emerged. Klaus sings aloud for the hearing and the ladies sing with their hands for the hearing-impaired. They actually sign the songs with their entire body—there is comprehensive interaction between hands, facial expression, posture of the head and the body.