They are cultural assets. Art-historical jewels. Anyone who reads Helmuth Bischoff’s book realizes that the most excellent mangers can be found in smaller municipalities. And without the commitment of some people they would have long been lost. The travel editor Helmuth went on a search for these mangers in the Palatinate and wrote a book full of art stories. This is a conversation about unexpected treasures and why an entire village has become followers of the manger cult.

When Christmas is approaching, he first looks for moss. Karl-Heinz Wiesemann, bishop of the diocese of Speyer, goes out into the forest and looks for things that his manger still needs. Afterwards, he installs the nativity scene and then spends the entire evening just “watching it and marvelling at it.” It doesn’t usually happen that a bishop gives personal insights into his living room at the beginning of a Christmas letter to his parish and talks in detail about how he sets up the manger from his childhood every year with a new arrangement for the manger and then eventually just sits in front of it in contemplation. The travel editor Helmuth Bischoff from Heidelberg, who has written books about the Rhine-Neckar region as well as about Barcelona, has managed to present the stories of Palatinate mangers with their special characteristics and their origins while portraying the people with whom they are connected. The result of his research is a beautifully designed book with photos by Norman P. Krauß that was published by Kurpfälzischer Verlag.

Wo Sonst: Why are there so many special mangers in the Palatinate?

Helmuth Bischoff: The Palatinate used to belong to Bavaria for a long time and so you find a large number of mangers here that were made by Sebastian Osterrieder (1864–1932) from Munich, who is deemed to have revived the idea of the Christmas manger after it had become unpopular in folk art due to secularization until in the early 19th century. Sebastian Osterrieder contributed much to its new popularity in the early 20th century. He achieved this particularly through a manger he made for the German Emperor Wilhelm II, serving him as starting point for a manger-making career.

What makes the mangers made by Sebastian Osterrieder so special?

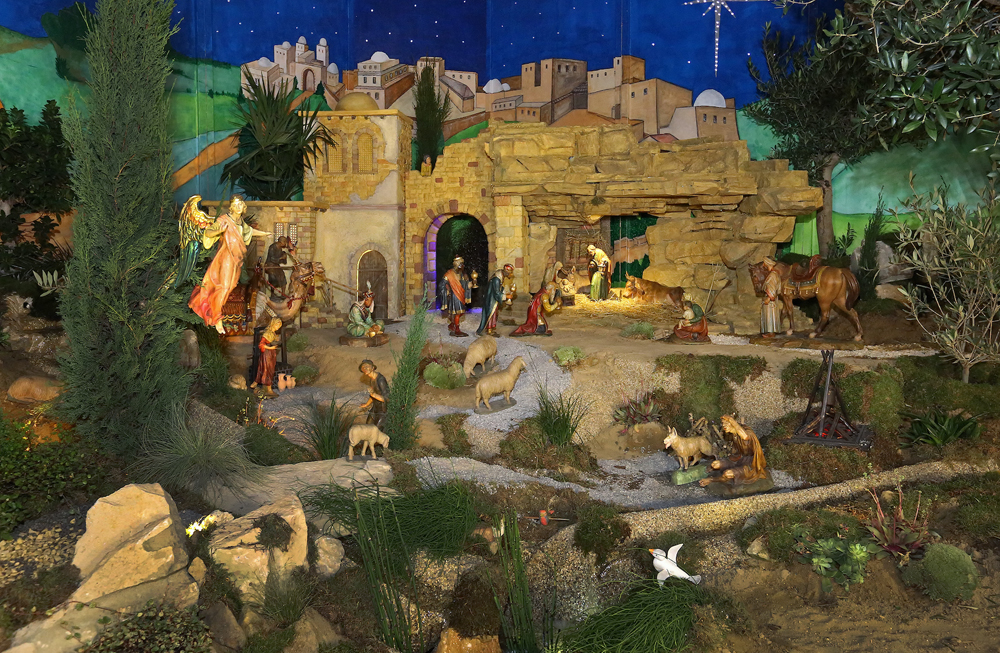

Helmut Bischoff: The figures are shaped vividly and naturally. Other figures made of papier-mâché or of wood are just not like the ones by Osterrieder. He had developed a special method of casting figures using plaster, chalk from Champagne and animal glue—a method that became popular as ‘French hard casting.’ This way, the shapes of clothes and faces are fluid and natural. Bodies closely resemble human physiognomy. Robes fall like they actually do in reality. You couldn’t achieve this with woodcarving. There would always be rough edges.

And where can you find these Osterrieder mangers?

Helmuth Bischoff: Well-preserved Osterrieder mangers are located in the St Maria church in Landau, in the Mauritius church in Erfweiler-Ehlingen, in the Blieskastel castle church, in St Maria Himmelfahrt church in Herxheim and in St Hildegard in Sankt Ingbert. And there is the one in St Peter in Hettenleidelheim.

Why did one of the most important manger makers have so many assignments in the Palatinate?

Helmuth Bischoff: Apparently, Sebastian Osterrieder had met a priest from Deidesheim, who recommended his successor to buy an Osterrieder manger. That was the beginning. And Osterrieder’s sister spent her twilight years in a convent home in Herxheim—maybe this was his actual connection to the Palatinate.