The museum of technology was an idea born at a regulars meeting, says press spokeswoman Simone Lingner. Some technology enthusiasts met in late 1980—among them the entrepreneur Eberhard Layher. They shared a passion for old vehicles and a common problem: far too little space for the carefully restored jewels. So they decided to rent a large hall—and make it accessible to other technology enthusiasts in order to counterfinance a part of the rent. The museum was opened on May 6, 1981 and attracted a growing number of visitors each week. In 1991, the museum opened a second exhibition area—the Technik Museum in Speyer. Eberhard’s son, Hermann Layher, assumed the management post for both locations. The exhibition area in Sinsheim has grown from an initial 5,000 to over 33,000 square metres today. The new hall no. 3 was opened only recently, in the past year. It bears a special exhibition about the ‘Mythos Alfa Romeo’ (legendary Alfa Romeo).

“We could easily fill another three halls”

The responsible body of the two museum locations is the club Auto + Technik Museum Sinsheim e. V. with over 3,500 members across the globe. Most of the exhibits are the members’ property and are given to the museum on loan. And, almost on a daily basis, more people get in touch with the museum and offer their vintage car, motorbike or old tractor. “We could easily fill another three halls,” says Holger.

The special exhibition about the ‘Mythos Alfa Romeo’ (legendary Alfa Romeo).

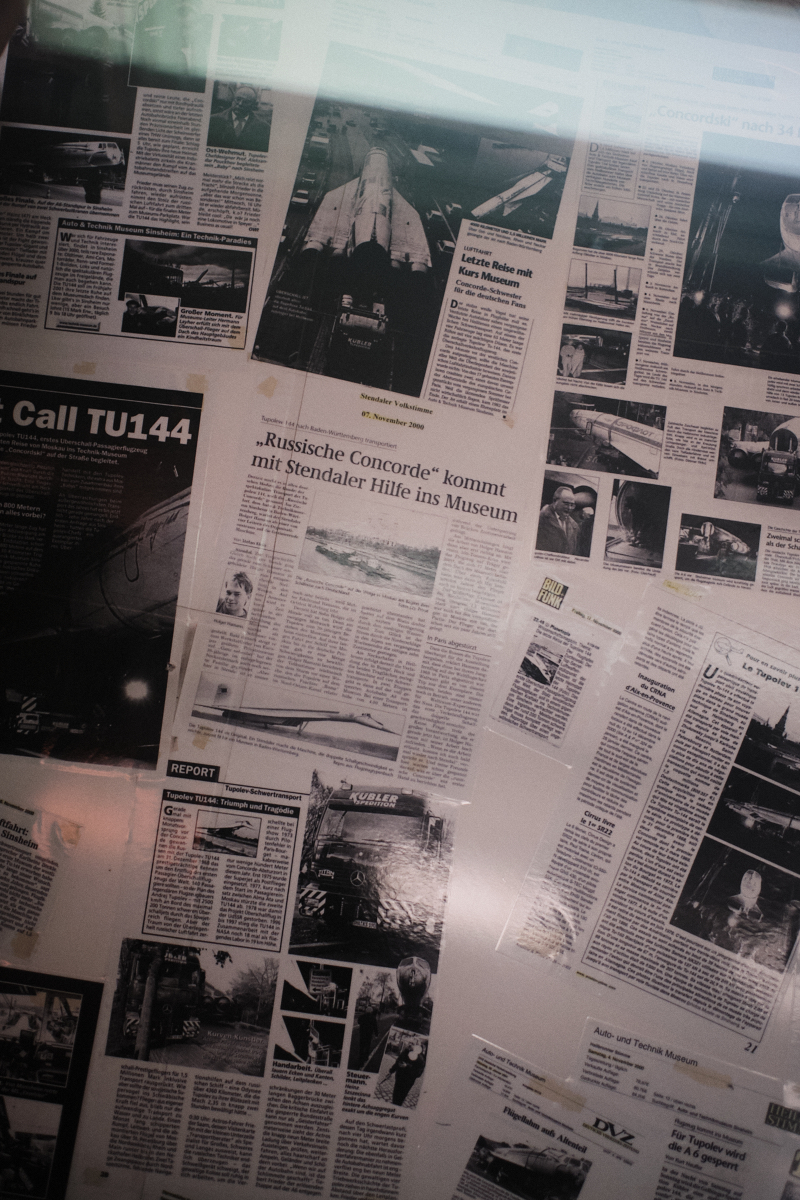

He came to the region in 1990. He had worked as a skilled mechanic in a metalworking company. “I didn’t like that. It was very monotonous—just bending metal plates every day.” In 1991, he read a newspaper advertisement: The Technik Museum was looking for a mechanic. “I’m really into motorbikes and I applied for the job straight away.” Successfully so. Five years later he even became the manager of the workshop. He doesn’t bend metal plates anymore. He flies around the world instead and picks up a Tupolev Tu-144 from Russia and accompanies the Concorde F-BVFB on its final journey. He organizes, solves problems and—makes things possible.

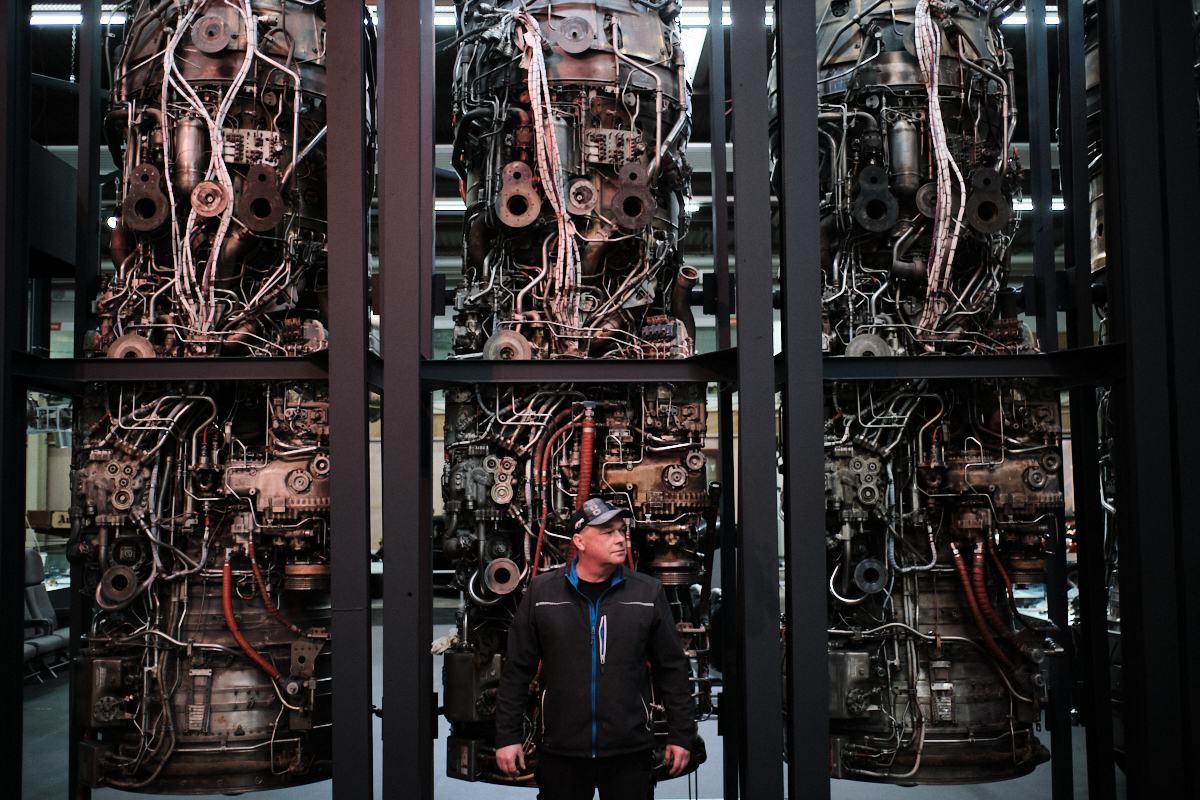

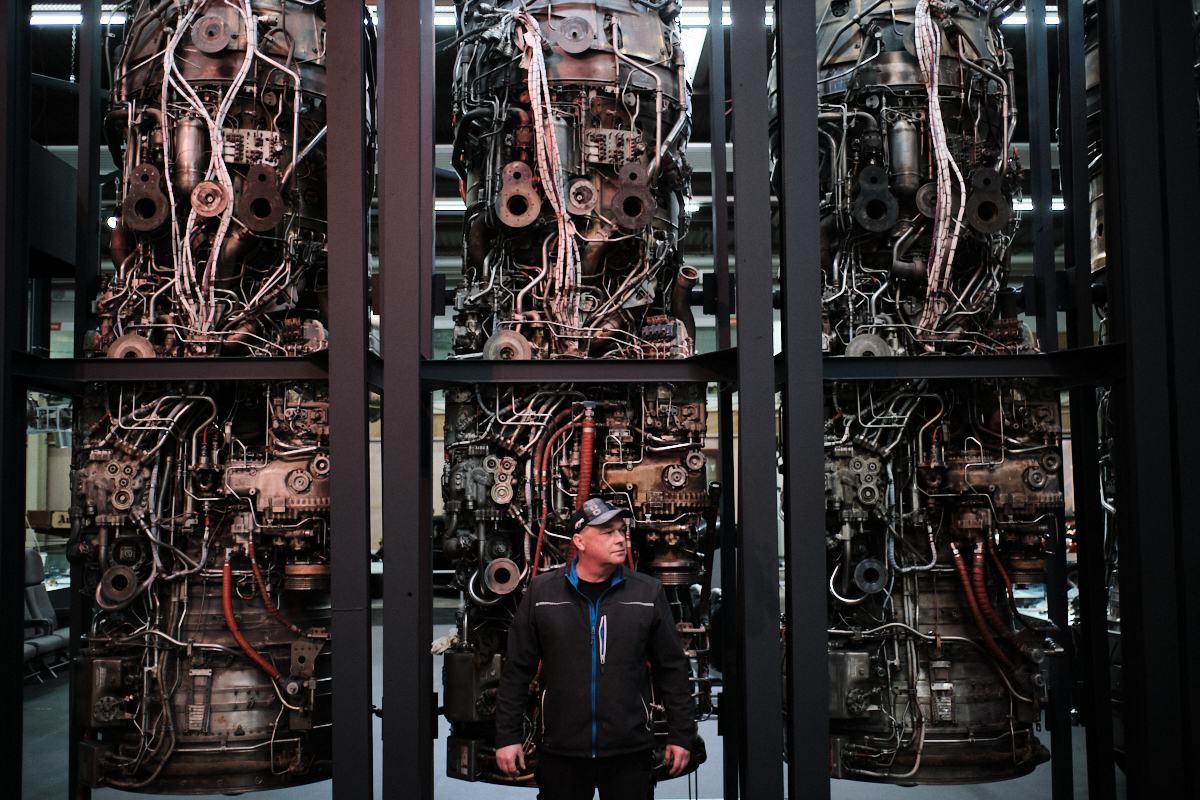

Holger stands in front of the engines of the Concorde.

Now, he stands in front of the engines of the Concorde, located below in the hall. And here, he goes into raptures about the transportation of the aeroplane—a spectacular mass event. “This was and will remain the most beautiful event I witnessed,” he says. Straight from its landing at Baden-Airpark after her last flight, the Concorde brought her environment to a standstill. “The roads were crowded, people everywhere,” Holger describes the scene. They released the remaining kerosene from the tank right at the airport: “To accomplish this, we let the engines run while the Concorde stood at the ground—at full speed.” He can still feel, he says, how the ground was shaking and a roaring filled the air and even the chest. Holger is wallowing in memories and superlatives. “Thrilling, unforgettable,” is what it was like. And it remained this way the entire route to Sinsheim. No matter whether the plane was carried along waterways or, for the last kilometres, along the motorway—there were people everywhere. “Even at three in the morning! You couldn’t even take a pee, because you couldn’t hide from them in the bushes—somebody would sit there to watch the plane.”

The museum in Sinsheim is the only place in the world where you can see the two former competitors in terms of supersonic speed, Tupolev and Concorde, next to each other.

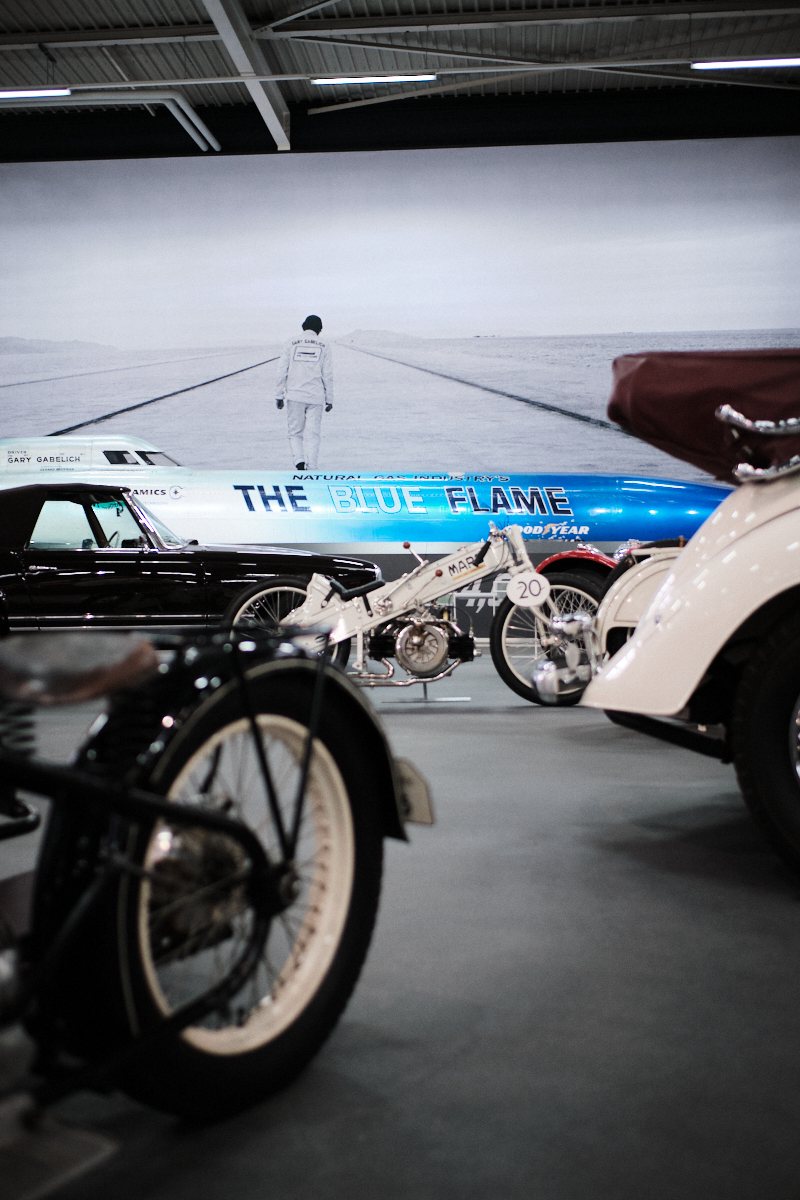

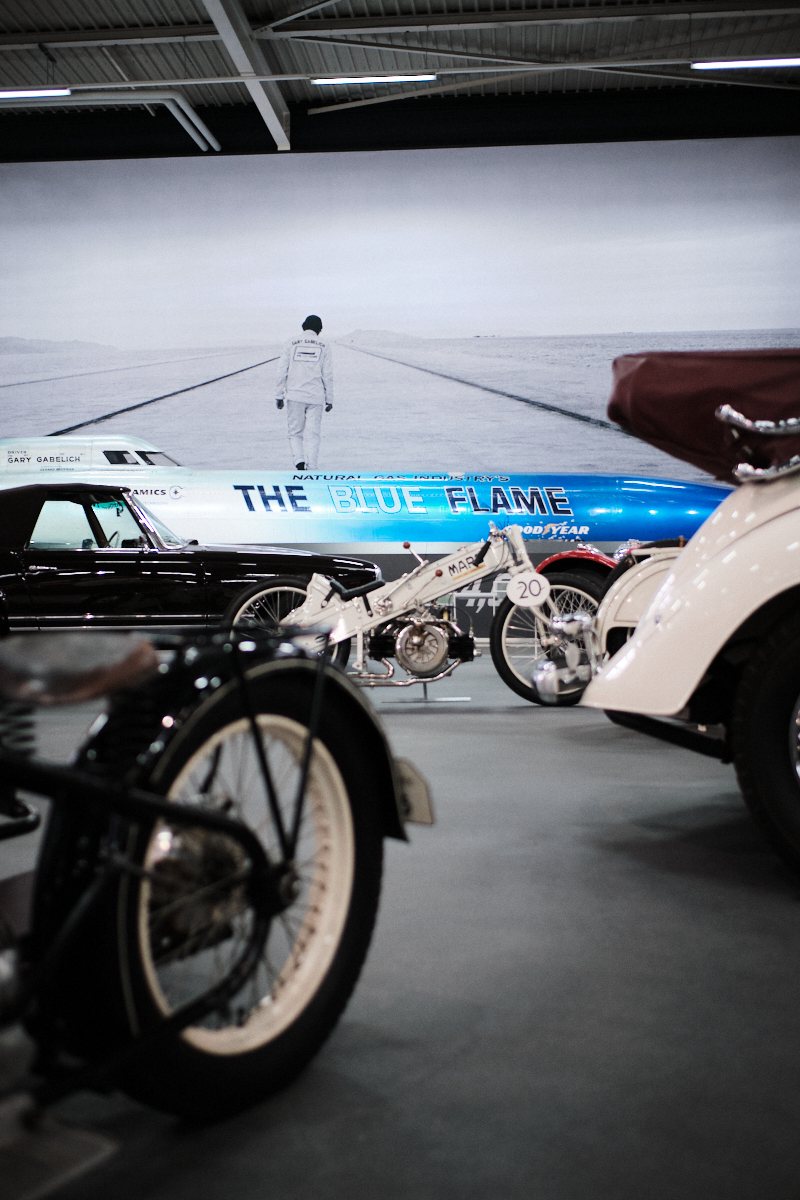

The museum in Sinsheim is the only place in the world where you can see the two former competitors in terms of supersonic speed, Tupolev and Concorde, next to each other, towering into the sky from the building’s rooftop. But this is by far not the only specialty the museum has to offer. It holds, for example, the record-breaking vehicle ‘The Blue Flame’. This mixture between a car and a rocket carried the American Gary Gabelich, as first human, at a speed of over 1,000 kilometres per hour. His family keeps coming to Sinsheim every now and then. “It’s great fun to see Gary’s grandchildren standing here watching the vehicle that their grandpa rode,” says Holger.

The record-breaking vehicle ‘The Blue Flame’.

Such visitors are common here, both in Sinsheim and in Speyer—people, who have a unique relation to a certain exhibit: the Concorde pilot, a Tupolev engineer, a submarine captain. They all take a stroll down memory lane here from time to time. They, just like the large number of club members, know that the precious technology, planes just as much as dance organs, is in safe hands here—with people, who are just as committed and passionate as the roughly 650,000 visitors to the museum per year.

This passion can best be experienced on Brazzeltag day in Speyer, which takes place annually on the second weekend of May. On Brazzeltag day, the museum exhibits are given a new lease on life: Brutus and Brutussi for example, motorized Bobby Cars, or a historic fire engine. It is “a huge playground for tech fans,” as Simone Lingner puts it. This stage-managing requires a good amount of professional expertise, however. “We are not for nothing the only team in the world that has disassembled a Boeing 747 and screwed it back together again,” says Holger. “Even though Boeing themselves said that this is not doable.” But this kind of statement has of course never been able to hold his team back as of yet.

https://sinsheim.technik-museum.de/en