For more than forty years, Dr. Ludwig von Heyl cultivated potatoes in Bobenheim-Roxheim, today his commitment to the “Pälzer Grumbeer” (Palatinate dialect meaning “Palatinate potato”) shows itself in a different way: He is now the boss of Germany’s only potato museum in Fußgönheim.

A quick glance at the old wooden shelf and you get an idea of what might be in store for a potato: iron ricers, mashers, graters. If only they could – these old kitchen tools in Fußgönheim’s potato museum would tell some rather wild stories. Stories from times in which the potato had to save the people of this region from starvation. “As a farmer you are inevitably connected to the potato,” Ludwig von Heyl says. And it is this connectedness that he dedicates himself entirely to – as the chairman of the association “Deutsches Kartoffelmuseum” (German potato museum).

The museum at a historical site: Fußgönheim’s former synagogue, built in 1842, was renovated in 1996 by the municipality and the association of the potato museum for about one million Deutschmark funded by public subsidies and to a large extent with the help of their own resources as well as donations from members of the association.

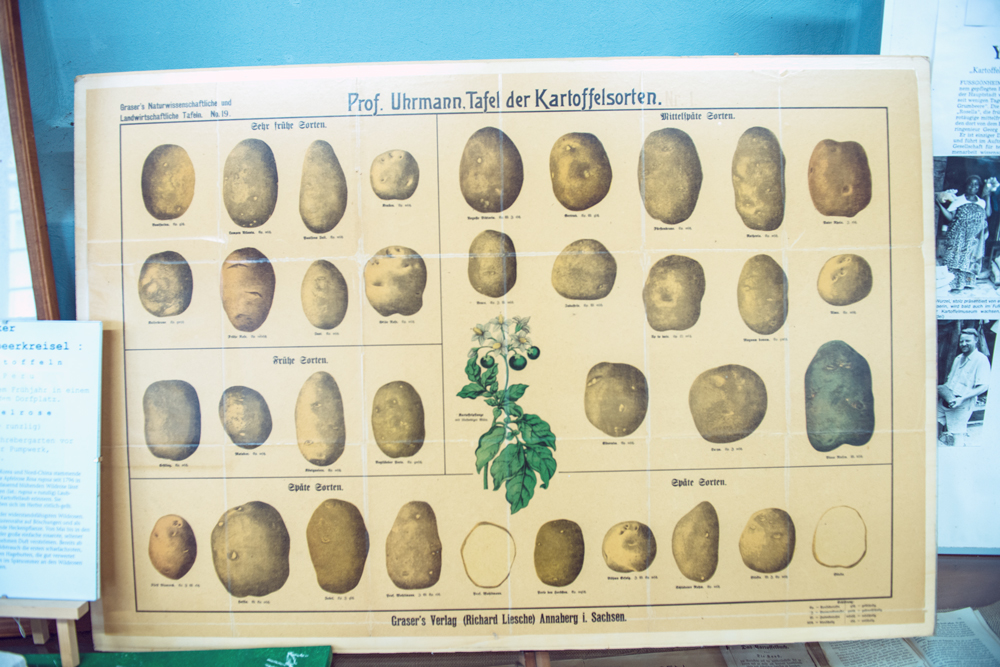

The little village with the stately castle Hallbergsches Schloss dating from the 18th century is situated to the west of Ludwigshafen in the Rhein-Pfalz-Kreis, a district in the east of Rhineland-Palatinate. In spite of its closeness to the city that produces chemicals the contrast could not be greater: The town with its round about 2,500 inhabitants is highly agricultural in character and in the vast fields surrounding it the potato plays a major role. In the former synagogue of the village the members of the association erected a memorial in its honour displaying roughly 1,000 exhibits. Ludwig von Heyl raves about the building, the high ceilings, the windows, the wall paintings. There is a lot to see in the exhibition room: information panels, display cases and cabinets stand closely together forming a line. Preserved potatoes, kitchen tools, rarities everywhere.

In the potato museum you are also informed about the migration background of the potato having arrived in Europe from Peru only about more than 400 years ago.

It was not so easy for the potato, as a glance into an old book reveals: “Church dignitaries called it ‘the devil’s fruit’, doctors voiced their misgivings with regard to its consumption, and peasants justified their reluctance in growing them by hinting at the fact that even dogs rejected raw potatoes.”

More than 40 years of potato experience: Ludwig von Heyl, the new chairman of the museum’s association.

Today, no-one wants to hear anything of that kind anymore. The Palatinate “Grumbeer” has long since become a culinary cultural asset. According to the producers association, the Palatinate region is the biggest coherent cultivation area of early potatoes in Germany. For the “Palatinator,” the Palatinate language artist and brand ambassador Chako Habekost, one thing is absolutely certain: “No matter if prepared as “Gebredelde” (Palatinate dialect meaning “roast potato”) or “Gequellde” (meaning “jacket potato”), as “Stambes” (“mashed potatoes”) or exotically in the wok – the “Grumbeer” from the Palatinate region is always present when it comes to enjoying culinary delights.”

Ludwig von Heyl is listening attentively while Karl Freidel, the potato museum’s good soul, explains, how the historic potato peeling machine works: a construction with four toothed wheels screwed on the table top. It has quite a brutal appearance compared to today’s potato peelers. “I don’t know everything yet,” 67-year-old Ludwig von Heyl admits. He studied agricultural engineering at the Technical University in Munich, later he earned his PhD in agricultural technology. He ran the Nonnenhof, his family business in Bobenheim-Roxheim for four decades. Von Heyl does not have to think long about it: He cultivated 2,000 tons of potatoes each year. For four decades.

“The potato grows in the soil just like that – as a farmer there is not a whole lot you can do about it.”

In front of the display case showing measuring and testing instruments Ludwig von Heyl shakes his head knowingly. “It is a strict business,” he says remembering the many hundredweights of potatoes the quality of which had to be tested. For two years now, he has not had to confront himself with strict testers any more: His son now runs the Nonnenhof and grows grain. Sugar beet, carrots and spinach, too. But: no potatoes. Doesn’t the museum director’s heart bleed? “Not at all,” the father says. “I leave him free to make his own decisions.” The fact that the “senior” was playing the role of the backseat driver for too long was a far too common mistake in family-run businesses.