There was a time when walnuts were just as important as apples in the Odenwald. Then wars decimated the number of trees, orchard meadows became less profitable and French varieties flooded the market. The trees fell into oblivion. Marion Jöst works as an environmental consultant for the municipality of Rimbach. By creating a new variety, she wants to get Odenwald locals excited about walnuts again.

On this cloudy Saturday in autumn, Marion Jöst stands under the tree that started it all. It’s been more than 30 years since she first climbed the steep meadow in Unter-Mengelbach. She bends down and picks a walnut out of the grass. It looks like just another nut to the untrained eye. But for Marion it is unique. “An average nut has a point and a curve, similar to a chicken egg,” the short woman explains while her reddish-blonde curls are bobbing in the wind. “This one has two points. This makes it easy to recognise. And it is why we made it the Rimbach nut.” Marion places the nut between her hands and gives it a good squeeze. It cracks. She picks out a piece of the ivory-coloured interior, pops it in her mouth and beams: “And it’s really good!”

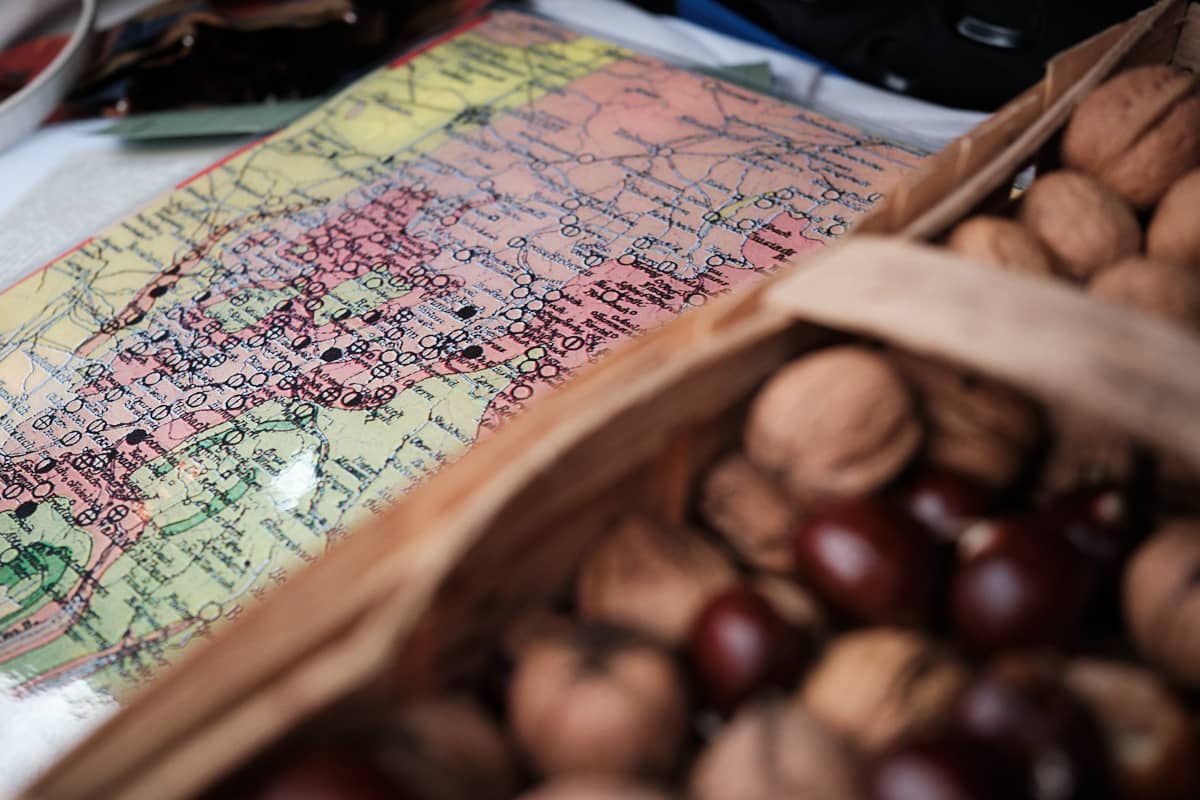

Mild yet intense is the flavour of the variety that the environmental consultant for Rimbach wants to turn into a local brand. Marion tasted it for the first time when she was less than 30 years old. At the time, the biologist, who grew up in the Ulfenbachtal valley, had just started her job in Rimbach. One of her first tasks was to map the natural environment in the municipality. She discovered an unusual number of walnut trees on her way to Unter-Mengelbach, a small hamlet at the foot of Tromm mountain. Marion wanted to know more about them and began to talk to the locals. Eventually she was led to Rudi Bangert’s tree. He told her the story of his walnuts, which he brought to the market in Weinheim until the 1960s. Then the traders no longer wanted them, because the nuts couldn’t compete with the larger, oilier French varieties.

Before that, walnuts used to be just as important as apples in the Odenwald. People journeyed as far away as Heidelberg and Frankfurt to sell them. About 300 of the trees with the deep taproots and spherical treetops grew in Rimbach and another 1,000 in Zotzenbach in 1904. There were probably even more a few decades earlier. The wars at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century had decimated the number of trees. Marion knows all about this because she has been researching walnut cultivation in the Odenwald ever since she made her discovery in Unter-Mengelbach. “Rifle stocks used to be made of walnut wood,” Marion knows. “This is why many trees were cut down during the Franco-Prussian War and the First World War.”