The depot is a part of the former mechanical workshops of the Deutsche Bahn in Heidelberg. Steam engines and waggons were repaired here until the 1980s. Afterwards, the building was vacant for almost 40 years. The same applies to the former Bahn water tower that rises up into the sky. The tank inside could hold 330 cubic metres of pure, lime-free water from the Königstuhl mountain. The last steam engine locomotive was tanked here in 1972.

“We knew right away that we had to get it!”

Some 42 years later, three architects tripped over dove droppings through the deserted rooms and fought their way through cobwebs. After ten minutes they knew: “This is it!” Stephan Weber starts to laugh when he talks about the day that he entered the Tankturm tower for the first time with his colleagues Stefan Loebner and Armin Schäfer. The trio had already brought new life to a number of old buildings, but always under contract to somebody else and never for themselves. “We knew right away that we had to get it!” Even though it was equally obvious that it’d be a colossal task.

The rebuilding took two years. “We wanted to retain as much as possible and show the building’s history,” Stephan explains. Inclusive of the damages and injuries it had suffered during the decades of vacancy. They only secured crumbling bricks. They painted neither over these bricks, nor over the rusty coat in the water tank, nor over the Second-World-War bullet holes in the eastwards façade. As a contrast, the architects wanted to apply radical stylistic change to the bits that required renewal. This is the case, for example, with the dramatic steel balconies that stick out from the tower—for reasons of fire safety. At another spot, instead of using bricks for repair work, they put a huge pane in the hole that an excavator had caused by driving into the façade. This way, they created bright and modern rooms, yet kept the tower’s history visible everywhere.

Architect Stephan Weber

From the beginning, the architects’ idea was to create more than just office space in the Tankturm. “We wanted it to become a meeting point for business and cultural life,” Stephan says. The time the three partners fell in love with the Bahn’s water tower coincided with the time the KlangForum performed at a city tour event of the architectural exhibition ‘Internationale Bauausstellung’. “We played in the railway underpass behind the workshop of the current Betriebswerk,” KlangForum manager Dominique Mayr recalls the scene. After the musicians had finished their performance, the conversation was, like so many times before, about the homelessness of the ensembles. “For decades, we have been doing our rehearsals at various places, even in a cellar of an old people’s home,” says the conductor. This made the intensive rehearsal, which he appreciates so much, very complicated. The organizers of the city tour had heard about the three architects’ plans and suggested to Dominique to contact them. He got in touch the same night and only a couple of days later he also stood between cobwebs and dove droppings with a torch and knew: “This is it!”

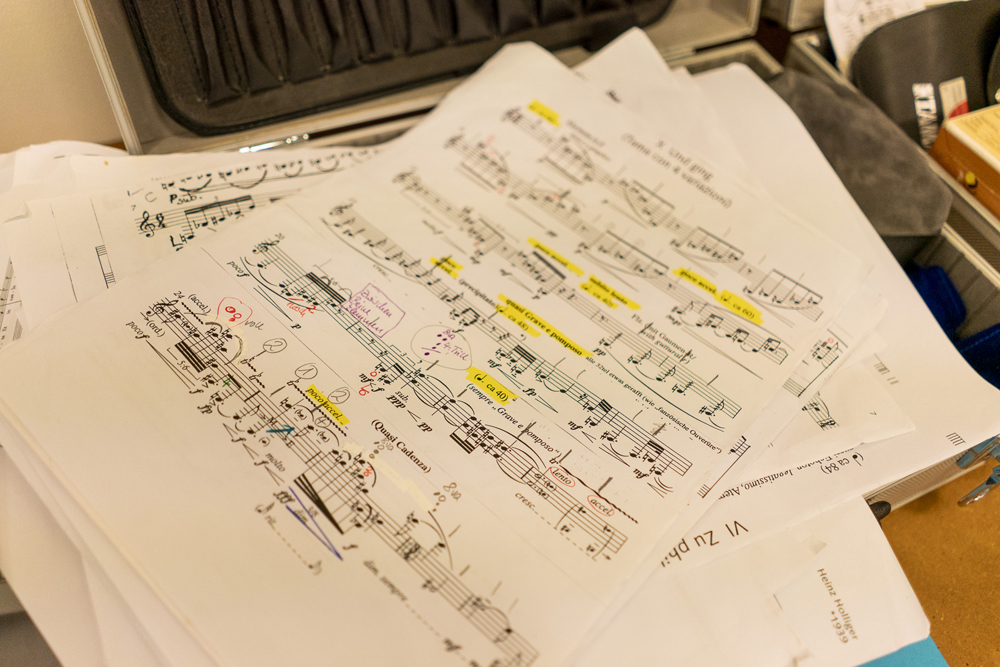

Dominique had warned the partners on the phone in advance: “We play contemporary classical music all day!” But Stephan and Stefan and Armin knew about the KlangForum and were looking forward to the cooperation. This way, the KlangForum musicians got to take part in the very conversion of the building and found even their first permanent home there in 2016: small rooms for individual rehearsal, bigger rooms for when both ensembles gather for certain projects, and also a great location for special concert experiences. “It is very precious to meet people whose interest extends beyond business—towards contents,” says Walter, because from an economic point of view there would have been renters that are much more lucrative than the KlangForum.

KlangForum manager Dominique Mayr.

The Tankturm acts as a catalyst for the KlangForum: The ensembles’ members come from throughout Europe to the region for certain projects usually, and much more appropriate rehearsal is possible now. “We were able to establish our own concert series and become more visible in city life,” Dominique explains. The KlangForum has excellent international recognition and performs at the Salzburg Festival or the Tongyeong International Music Festival in South Korea, for instance, it was, however, relatively unknown in its home region. “This has changed because of the Tankturm.”

And the tower has changed the architects’ lives as well. In 2018 they were awarded the Hugo-Häring-Landespreis by the Association of German Architects for redeveloping an industrial monument. The partners’ office had to be extended while inquiries by companies to rent the location increased. So they finally decided to rebuild the Betriebswerk maintenance depot some hundred metres down the railway as well—initially as an interim solution only. The KlangForum should be the main user of those rooms. Conductor Walter was not too enthusiastic about another move. After the first rehearsal there, however, he didn’t ever want to leave again. “It’s great to do rehearsal here.” Four glazed cubes unfold, like drawers, into the room that once hosted the locomotive repair workshop. Just like the architects, Walter identifies himself with the approach of retaining the old and to be as modern as possible where renewal is required. The resulting contrasts are not always easy to grasp. The architects often hear people commenting: “Oh, you haven’t completed your work yet!” and in a similar way, Walter knows that many people find new music taxing. “Music affects us deep inside, in our existence—so it cannot be just easy and pretty.” But many people have forgotten to listen. “However,” he believes, “you can learn to listen again,” in the rooms where steam engines were once repaired.

www.klangforum-heidelberg.de