The former fire station of the volunteer fire brigade in the Old Town Hall in Heidelberg-Handschuhsheim is only 46 square metres in size. Pushing its door open from the entrance in Mittlere Kirchgasse alleyway, you enter a world of fountain pens in a museum full of fantastic stories.

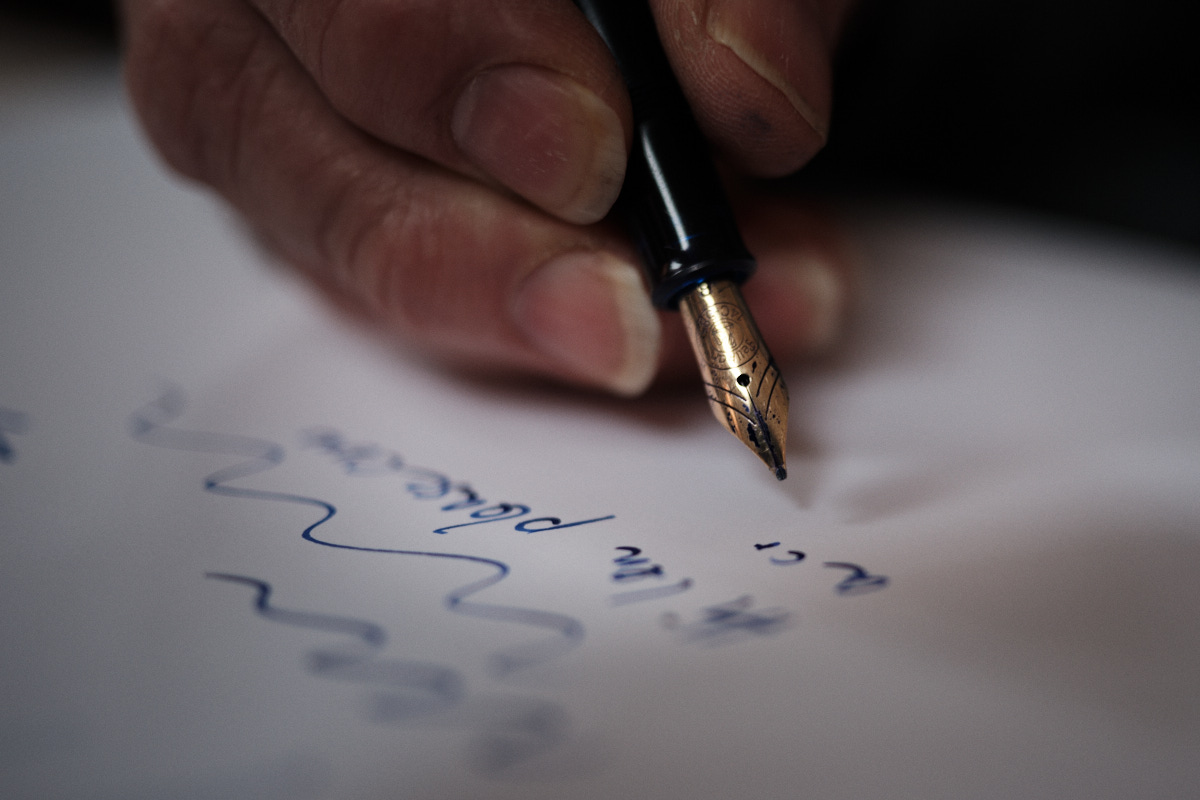

The guest book alone tells 1,000 stories. It is filled with texts and poems in many languages. Asian, Arabic and Russian characters alternate with small, enthusiastic messages in children’s handwriting. They are all written with the many fountain pens with which Thomas Neureither provides his guests. Writing is expressly encouraged in his museum in Heidelberg. Visitors can try out many of the pieces on display. The ingenious physics behind the leak-proof nibs are explained on oversized models at the amazement of the visitors. Sharpened bird feathers are dipped into imaginatively shaped, beautifully lacquered inkwells.

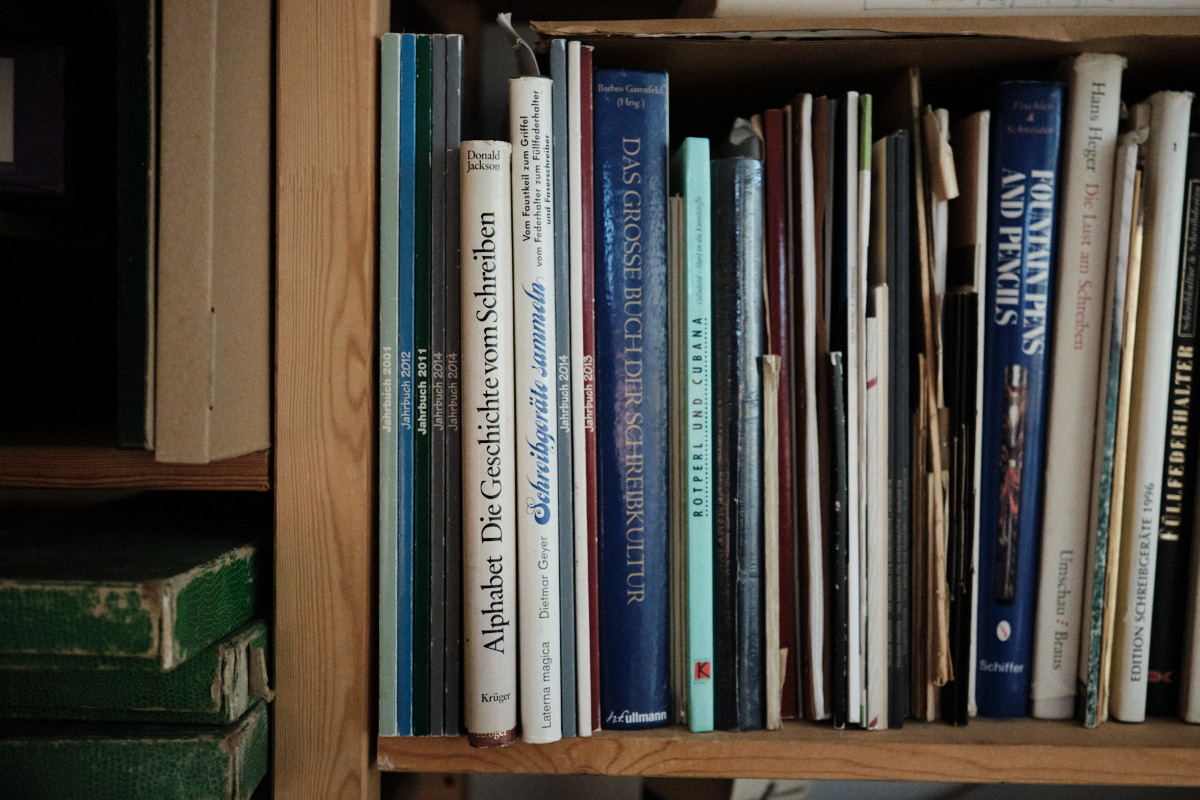

The museum attracts visitors of all ages and from all over the world. World-famous author Bernhard Schlink visited it once, too. Thomas, who founded the museum, stands at the centre of the collection. A Handschuhsheim neighbourhood association made the hall—specially renovated for this purpose—available to him in 2016. Since then, he has been displaying his private, extraordinary collection in his “Fülli” museum. It is an inexhaustible treasure trove of fountain pens, quills, ink bottles and barrels, a fully preserved workshop with tools, lathes and a guilloche machine for manufacturing and repairing fountain pens, as well as comprehensive, practically complete documentation about the around 40 former factories in the Heidelberg region, which used to be a centre of European fountain pen and nib production for decades.

Thomas has countless stories to tell. About the Perkeo fountain pen model, for example, which owes its name to its counterpart in Heidelberg Castle. “Both items have a huge filling capacity,” whereas the small black “war pens” made of cheap material, which were produced during the second world war due to a shortage of raw materials, are somewhat depressing. The story of Anne Frank’s lost fountain pen dates from then. An entry in her diary is revealing: “My fountain pen was always a precious possession.” She was never able to find out how it disappeared. After the war, very special pens with names such as Elégance or Monterosa were created, with virtually no limit to colours and patterns. The smallest model is a telescopic dip pen for women’s handbags, just a few centimetres long and decorated with floral engravings. Another tiny, brightly coloured women’s fountain pen used to be sold in a box together with a small purple inkwell.