From being a burden to being a place that makes a difference: In March 2018, the former “Ochsenpferchbunker” in Mannheim will become the MARCHIVUM.

Gloom? No, total darkness. What did it feel like in here, when the bombs were dropped outside? How did people cope—with the situation, with each other, with their fears? Did they panic when the power blacked out in here, behind meter-thick walls, in these rooms of the air raid shelter from 1940-1943? Ulrich Nieß is standing in the brand new MARCHIVUM in Mannheim, gazing into the sun. When the winter light fills the spacious new lecture room, they are definitely very far away—those dark nights of bombs being dropped during World War II.

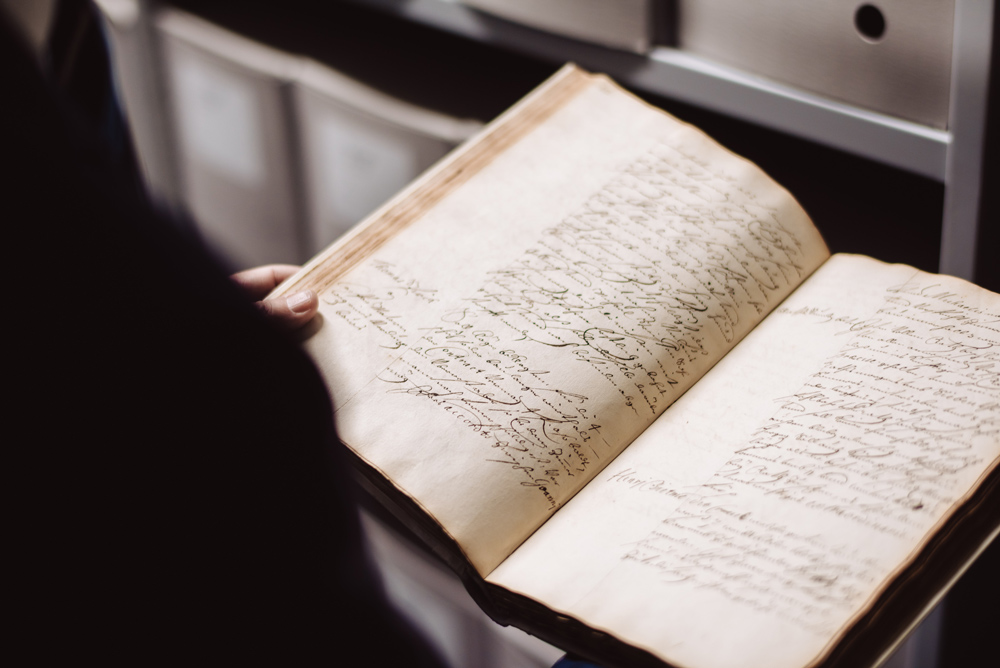

The “Ochsenpferchbunker” once used to be Mannheim’s biggest high-rise bunker: a shelter for 3,412 people; if ever necessary twice as many could squeeze in. Even after the Nazi era, it played a major role: as a refuge during Cold War times and right into the 1990s. After that, the relic from dark times had become problem property. Inaccessible, unused and so monumental that the concrete building block with its striking stair towers could hardly put into use anymore. But then, an idea began to evolve within Ulrich Neiß. “In 2013 we had water damage,” the director of Mannheim’s city archive says, remembering one morning in the Collini-Center which has housed the historical memory for almost three decades. There was no damage done, and yet: “Water is worse for archive material than fire.” In 2010, the archivist, who holds a doctorate in history, took part in a rescue operation unprecedented in archive history, helping to digitalise parts of Cologne’s city archive. “The images from back then never let go of me.” And since the city had wanted to get rid of its Collini-Center sooner or later anyway, he, too, started searching—for a suitable, a special place.

So it happened that this year, on March 17, 2018, MARCHIVUM opens. The unusual building was developed by the Mannheim-based architecture firm Schmucker, which had once brought up the idea of the conversion of the bunker and now works hand in glove with the city’s housing association “GBG Mannheim,” which will lease it to the city—a win-win situation for both parties. The costs for this project will amount to EUR 18.6 million, with the federal government covering EUR 6.6 million, because it considers it a “national project of urban building.” This is why Schmucker built two floors with glass fronts for offices, meeting rooms and a conference room on top of the former bunker. “The Nazis actually had already planned an extension,” Nieß says, showing the drawing of a Hitler Youth home, for which an elevator shaft had already been planned when the bunker was constructed. And the top ceiling had been arranged in such a way that it was especially easy to open. And yet: The Schmucker architects had to work without a construction file. The one from the Nazi era was lost, the federal government keeps its copy from the times of the Cold War still secret. This is why during the reconstruction works at some places true cabinets of curiosities were revealed—sometimes with 80 tons of sand behind. They were meant to serve as filter rooms with the sand cleaning the air in case of a nuclear attack. Sometimes they consist of tiny plots which were made after the war for families which had lost their homes. In the, back then, more than 400 social housings, it must have felt as if the sun light was completely out of reach behind those meter-thick walls and never-ending corridors, and with the air being so stuffy and wet.