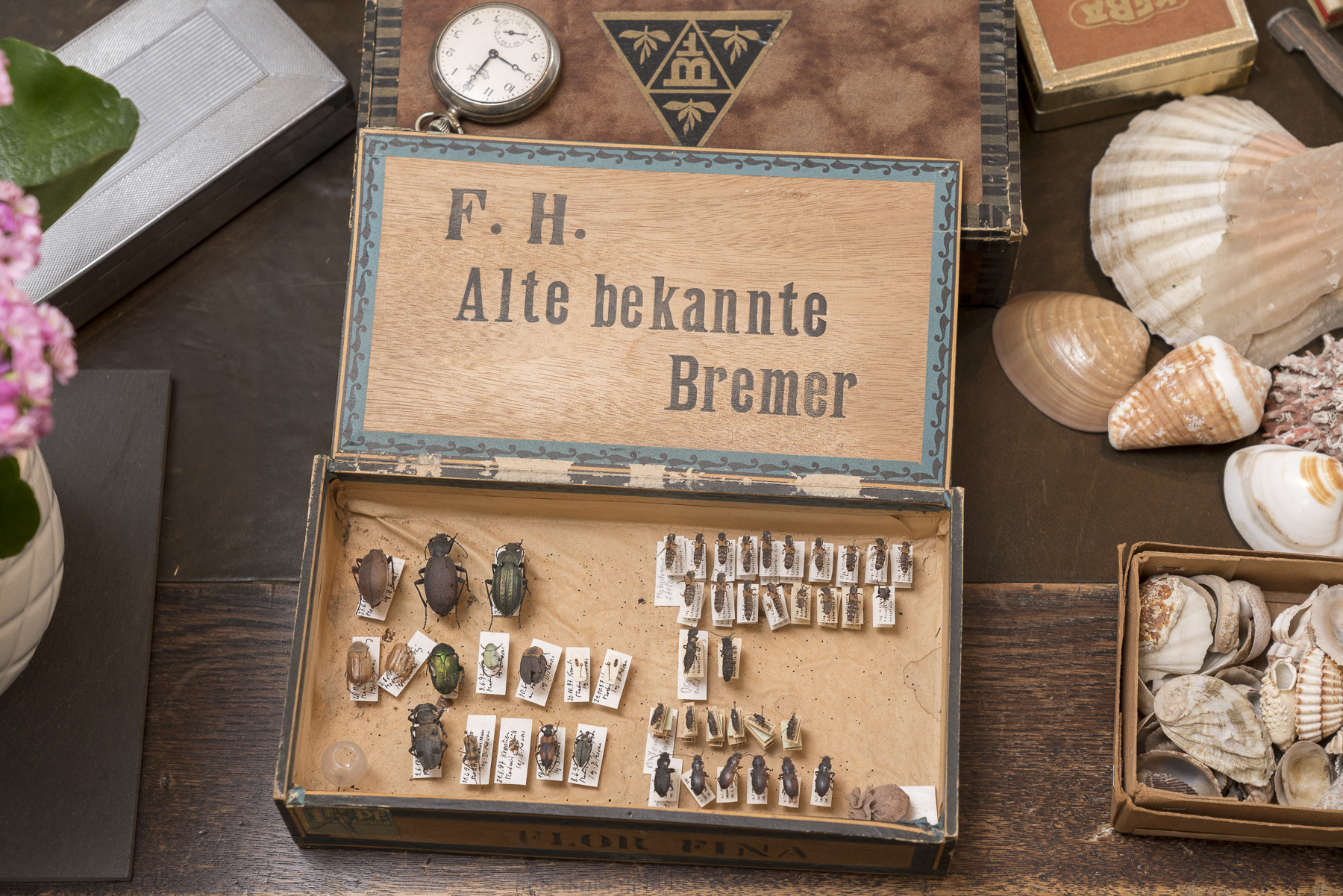

What is a museum building today, used to be Bosch’s garage building. The large dark-green gates would harbour the cars that a chauffeur took to bring him to his daily work in Ludwigshafen. Apartments for the gardener and the chauffeurs were above and next to the garages. Today, the building presents Bosch’s life to interested visitors walking through it. There is a high, dark, wooden table there with glass bottles and retorts placed on it representing the working environment of Bosch’s former ammonia laboratory in Ludwigshafen. On the first floor, a reproduction of his private office calls the chemist’s hobbies to mind. He had already been collecting insects when he was on his honeymoon and later, as the head of a corporate group, he tried to make time to look for little creatures on the ground around the original course of the Rhine, the Altrhein. He even used to reward employees with five Reichsmark for bringing him a rare beetle or butterfly species.

It is thanks to Gerda Tschira that visitors to the museum can immerse themselves in the life of Carl Bosch. The wife of the patron and co-founder of SAP Klaus Tschira was offered the purchase of the former garage building in 1996. She had just read the chemist’s biography then and decided to turn the house into a museum. “She researched in the entire German-speaking area in less than two years time and collected material, while having renovated the building and creating an exhibition,” Sabine explains. The Carl Bosch Museum was then opened on May 15, 1998.

“We have to maintain this passion and curiosity for the unknown in us as grown-ups as well”

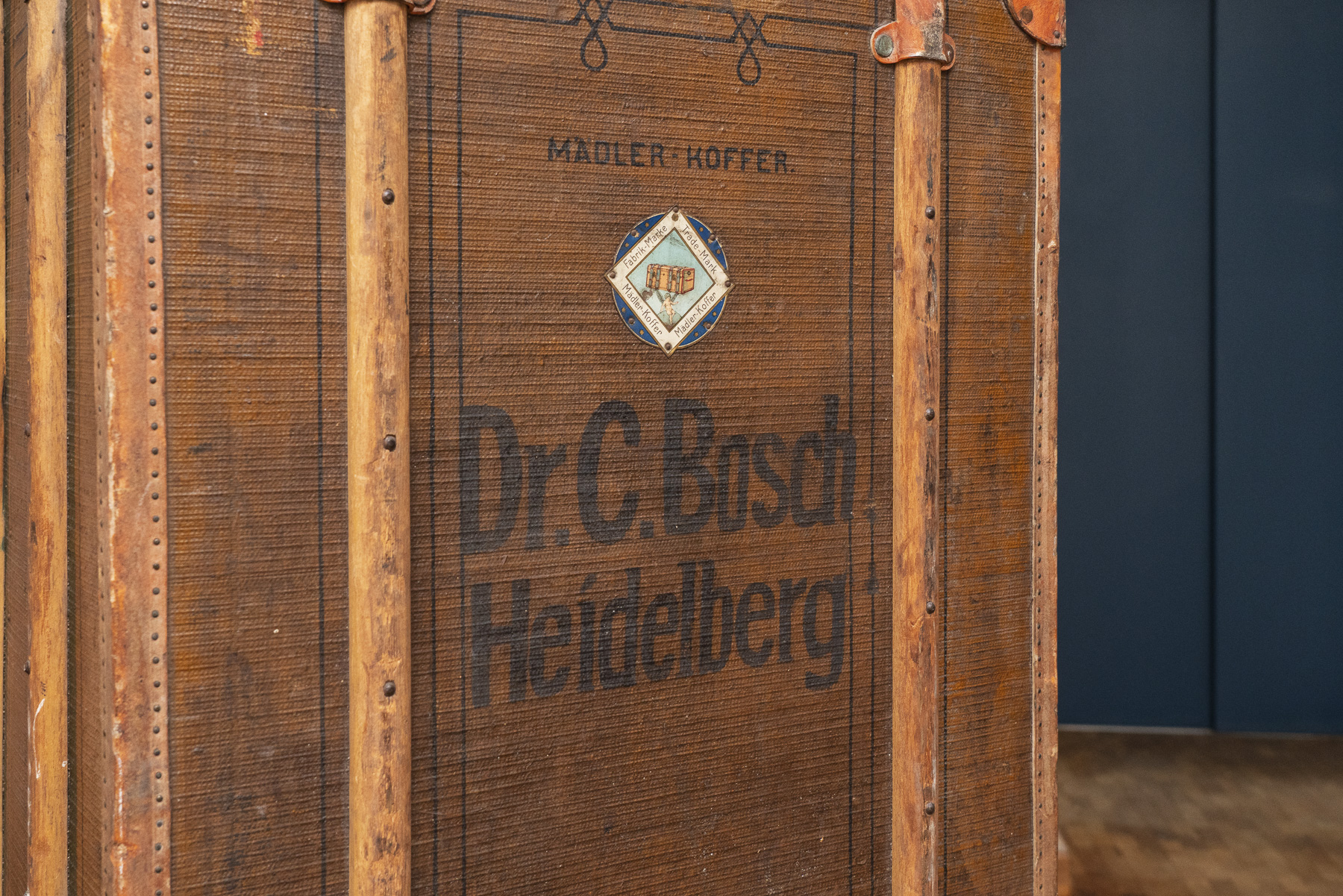

The exhibition is intended to reach a manifold audience, she says, “a nine-year-old just as much as his grandma.” There is a variety of experimentation offers for children of different ages: They can take a tightly packed suitcase and go on a journey back to the Carl Bosch period or construct a sherbet-powder fire extinguisher or a little electric motor. Adults interested in history can meanwhile immerse themselves in his biography and enthusiasts of chemistry in his scientific achievements. “We have to offer our children the joy and freedom of trying out things themselves and maintain this passion and curiosity for the unknown in us as grown-ups as well,” Sabine thinks.

Apart from this museum, the non-profit company comprises a mobile exhibition room called ‘Museum auf Achse’ (museum on the move) and the ‘Museum am Ginkgo’ (museum at the ginkgo) that offers space for educational purposes and special exhibitions. Its conspicuous and modern architecture is integrated well into the green environment and, at the same time, it constitutes a contrast to the historical garage building. The premises also have a café in store, where visitors can relax and let what they have seen while they sit sink in and have a freshly brewed coffee or cake enjoying the view of a sculptural art garden.

“Carl disassembled his mother’s sewing machine—he wanted to examine virtually everything”

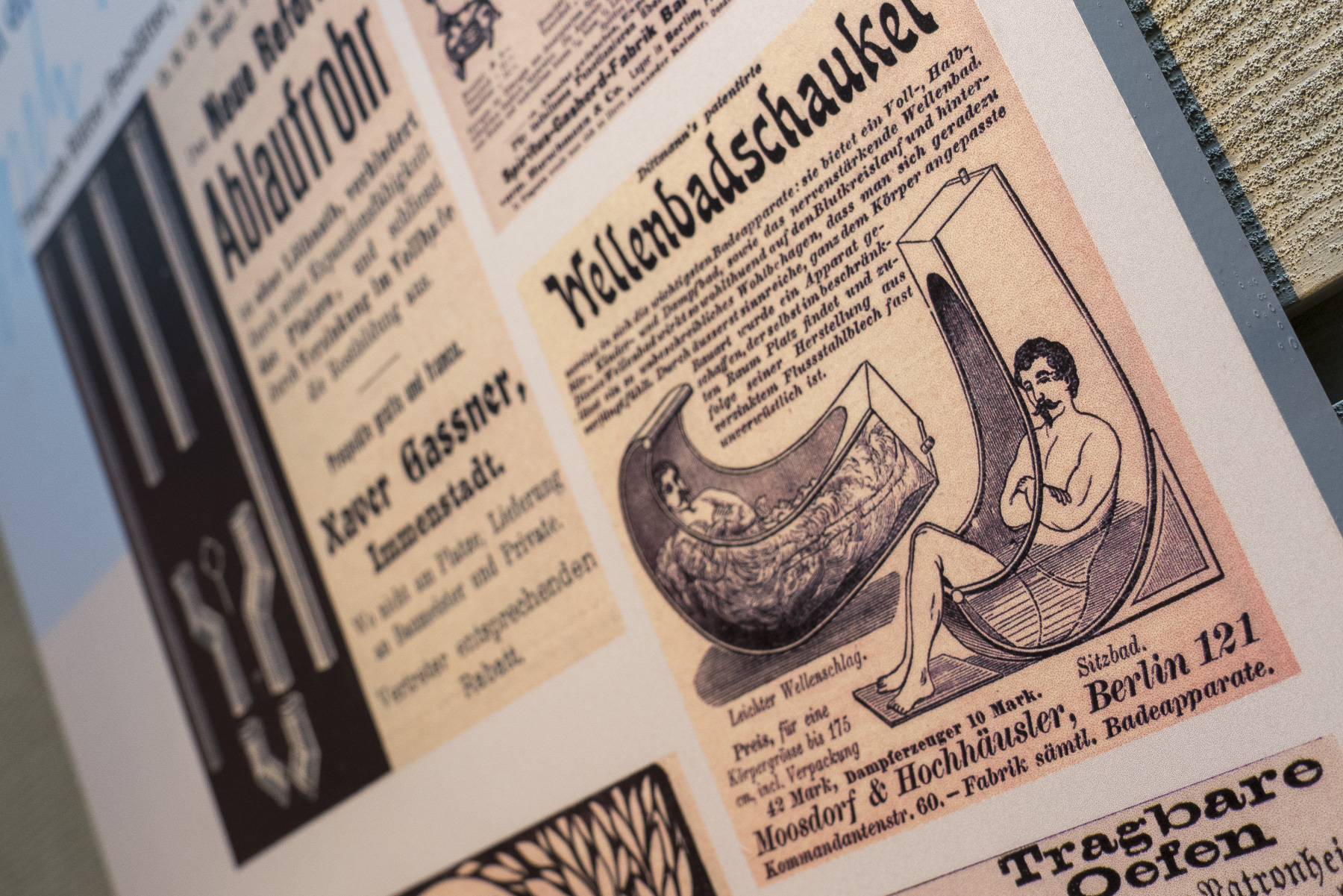

Sabine guides the visitors from behind the ticket desk up the narrow staircase to the first floor, where the tour through Carl Bosch’s life begins with a rocking bath and old tools from his childhood in Cologne, where he was born in 1874. His parents owned a wholesale business for installation requirements there and “Carl used to fiddle about and experiment from early on,” says Sabine. “Among others, he disassembled his mother’s sewing machine—he wanted to examine virtually everything.” In 1899, with a doctorate in chemistry in his bag, Carl moved to Ludwigshafen and signed on with BASF, which had been a chemistry company with global impact already at that time.

BASF – a chemistry company with global impact already at that time.

There, he managed to “bridge a huge gap” between basic scientific principles and industrial applications, as the Nobel Committee put it later. At the beginning of the 20th century in Karlsruhe, Fritz Haber had invented a process to produce ammonia and Carl Bosch further developed the basic principles for the purpose of its mass production. Visitors can marvel at the massive instruments and systems required for this process outside of the museum—they are too big for the rooms. The first system became operational in Oppau in 1913. The so-called ‘Haber-Bosch process’ contributed to feeding the worlds population, because ammonia was used as a fertilizer that brings nitrogen from the air into the soil, revolutionizing agriculture. Another side of the story, however, is that ammonia was used in the production of explosives during the First World War.

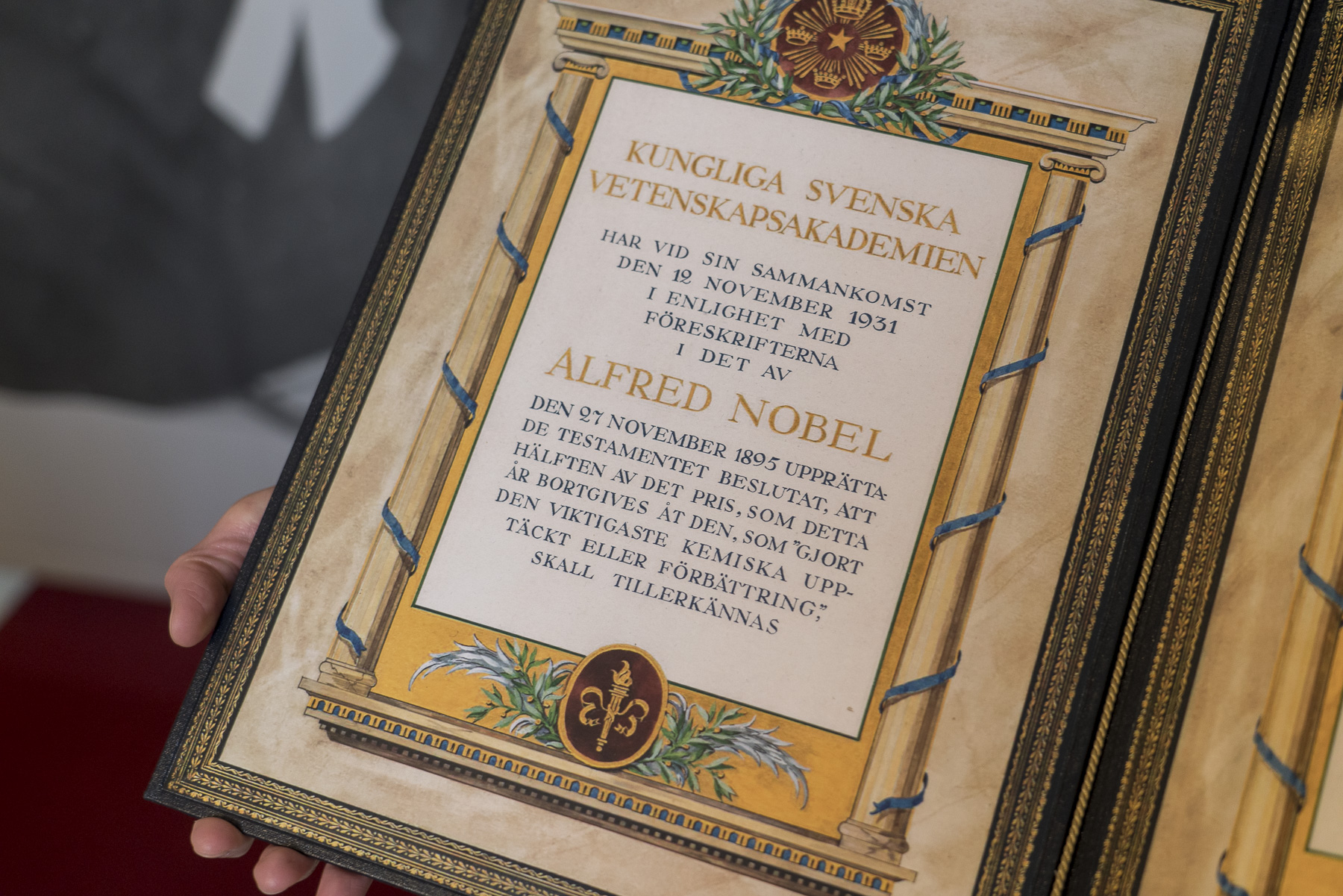

Following Fritz Haber, Carl was also awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of the Haber-Bosch process.

The exhibition tells the story of Carl Bosch’s rise to the top of the company step by step. He became BASF chief executive in 1919 and remained so even when the company was merged with IG Farben in 1925. In 1923, Carl moved to Heidelberg, to the expensive neighbourhoods at the slope of Königstuhl mountain with a view of the forest and meadow orchards, east of the old town. He lived in the grand building today known as the Villa Bosch, which now hosts the Klaus Tschira foundation, only a few hundred metres east of the garage building. In 1931, Carl Bosch, an already highly decorated scientist of his time, reached the height of his fame: Following Fritz Haber, he was also awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of the Haber-Bosch process. The entire family went to Stockholm to attend the ceremony. Carl’s wife Else later said that this was “the greatest event of their life.” But difficult and sorrowful years were to come.

“At least one meeting with Adolf Hitler is verified. It appears, however, to have ended in a disaster”

Carl observed the rise of the Nazis with mixed feelings. In the beginning he showed some approval of Adolf Hitler. At least of his employment policy, as Carl considered the prevailing high unemployment rate a major evil of the time. However, he became increasingly alarmed by the Nazis’ hostility towards science and by the persecution of Jewish scientists. “At least one meeting with Adolf Hitler is verified. It appears, however, to have ended in a disaster,” Sabine says. “They simply didn’t match.”

It was also due to the activities of the Nazis that Carl resigned from his post as chief executive of IG Farben in 1935 and joined the head of the supervisory board. Later he helped Jewish colleagues to escape the country—including the Austrian physicist Lise Meitner. Carl incurred the wrath of the rulers, when he denounced the restrictions imposed upon science by the Nazis in a speech in 1937. “It was probably his high reputation that saved him from being persecuted,” says Sabine.

The exhibition is intended to reach a manifold audience: “a nine-year-old just as much as his grandma.”

Physically weakened by diseases and emotionally damaged by the events of the 1930s, Carl Bosch died in Heidelberg on April 26, 1940. It is not only his professional accomplishments, which are reminiscent of him: In the town he chose as residence, his name is also associated with the foundation of the zoo; The possessions from his activities as an amateur scientist are preserved for posterity as well; His observatory’s telescope is used by the Astronomische Vereinigung in Tübingen (Tübingen astronomical association); A mineral collection is in possession of the Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian foundation in Washington; And his innumerable insects are an integral part of the Frankfurt Senckenberg Museum. Bosch’s long workdays will not remain in vain.

www.carl-bosch-museum.de